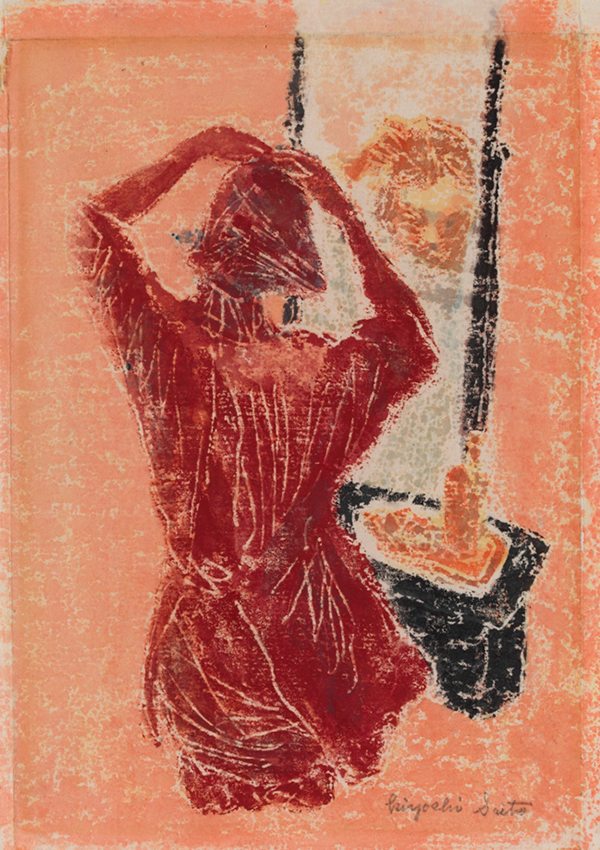

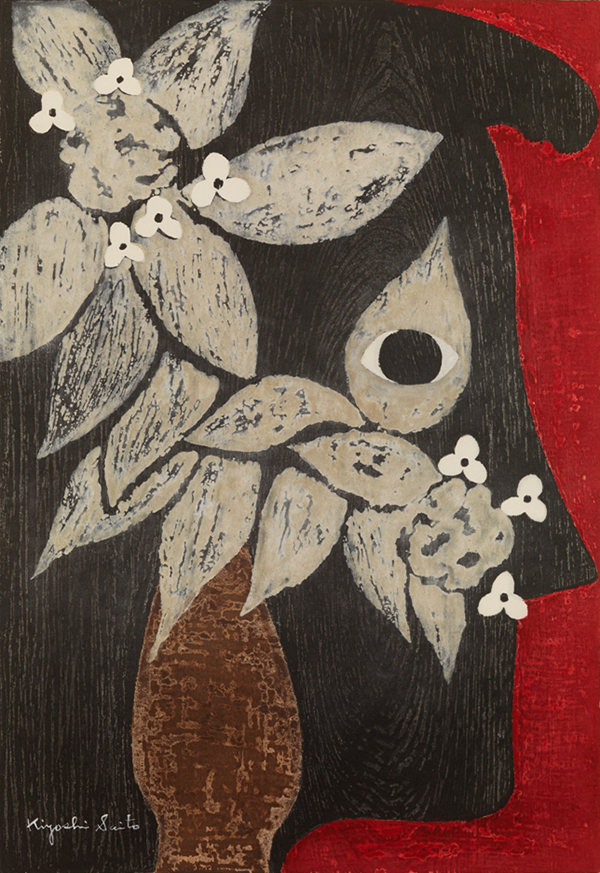

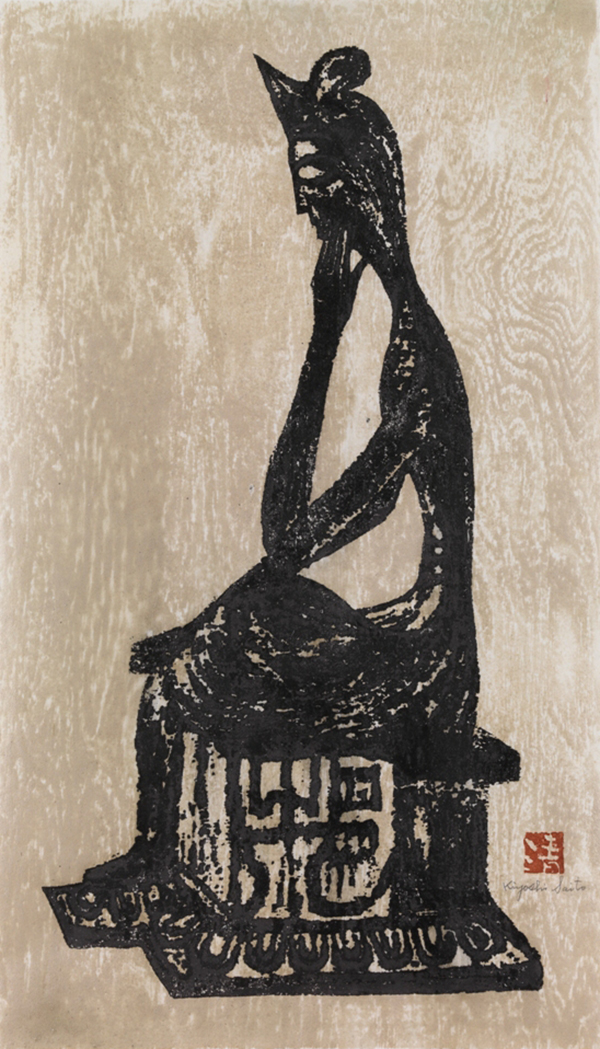

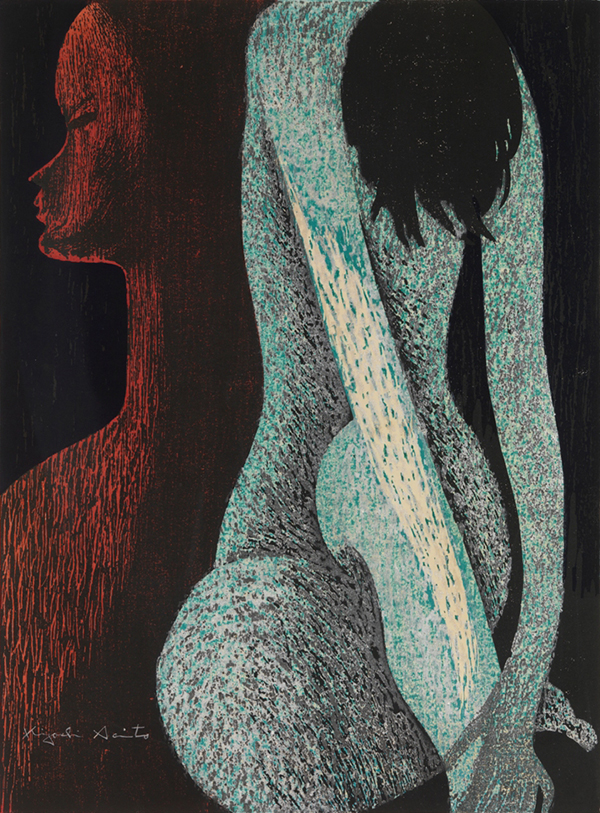

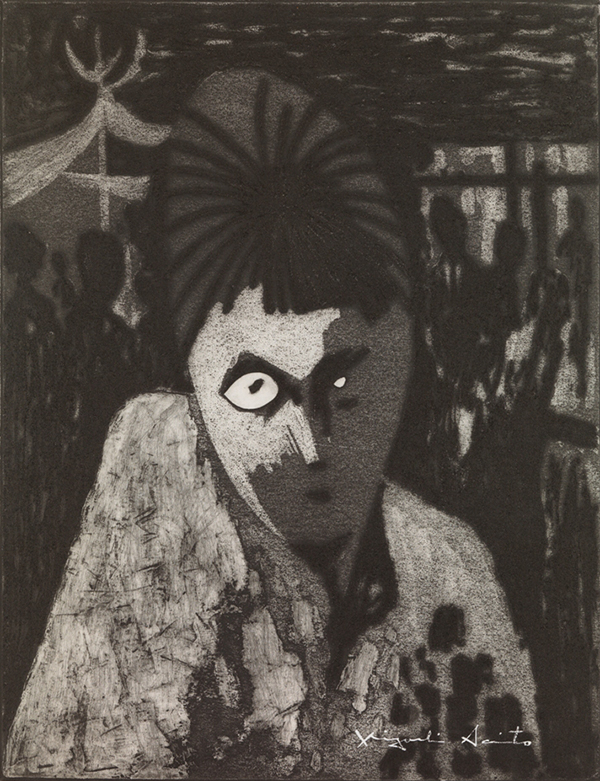

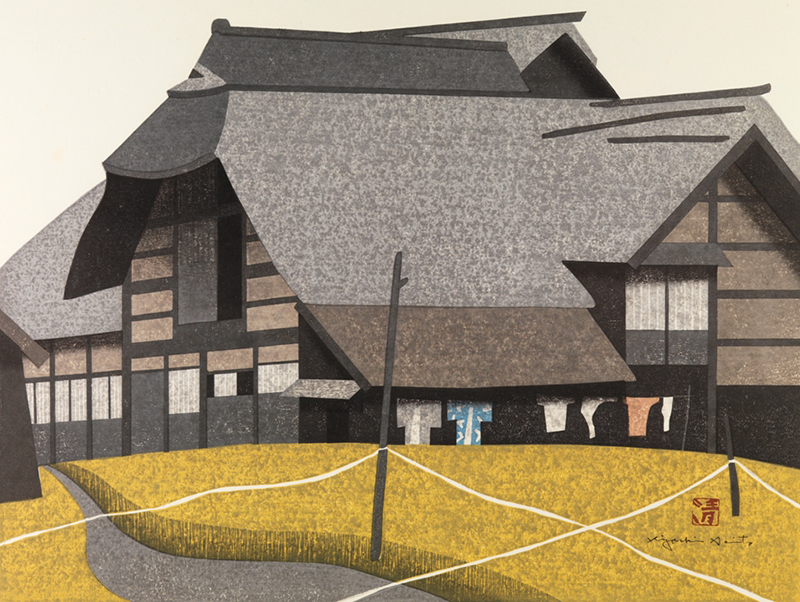

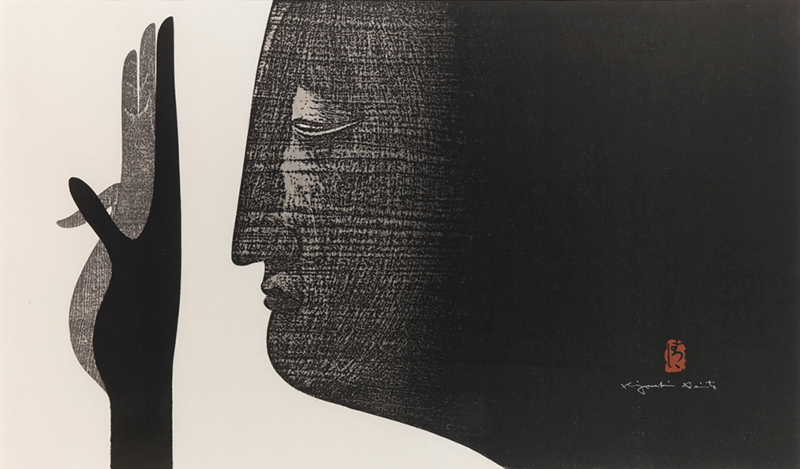

- Woman in My Native Village

- 1937

Woodblock print on paper

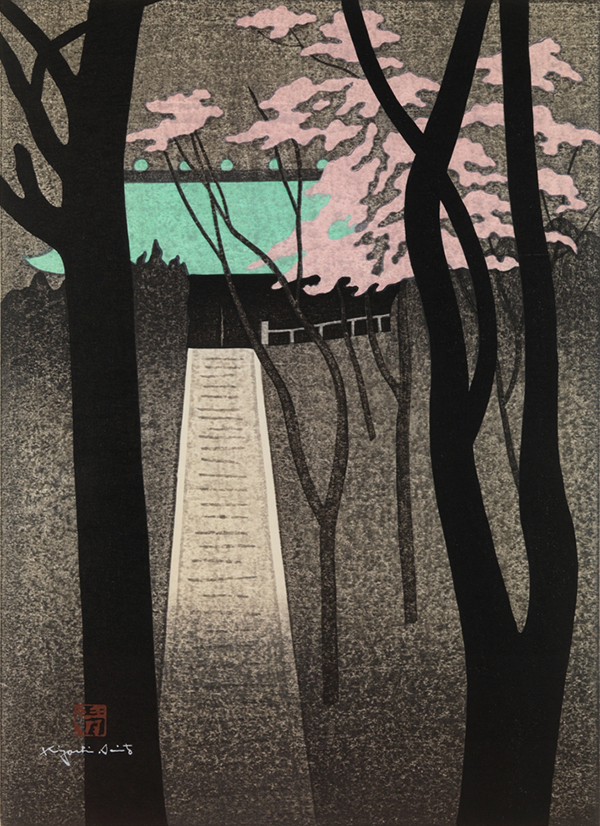

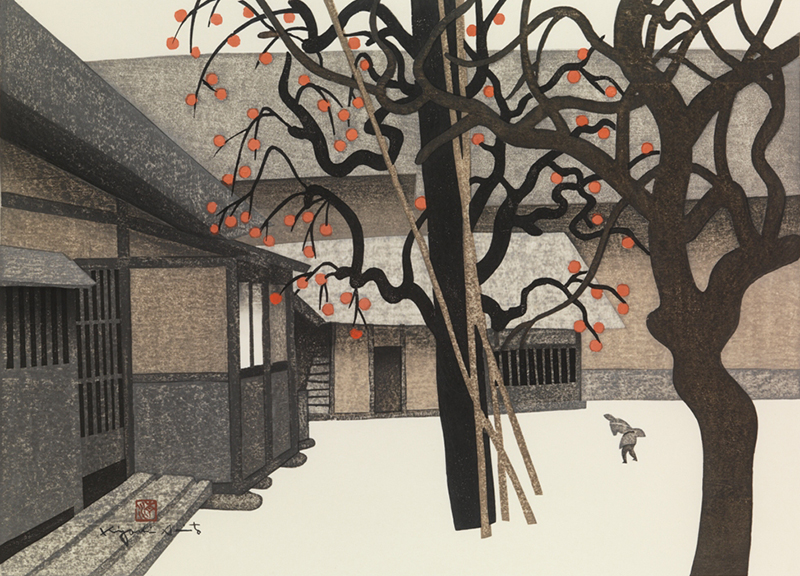

Entranced by art:

Saito’s encounter with

woodblock prints

- “I felt soothed when I was drawing”

- “The white spaces between the sign letters seemed strangely bewitching”

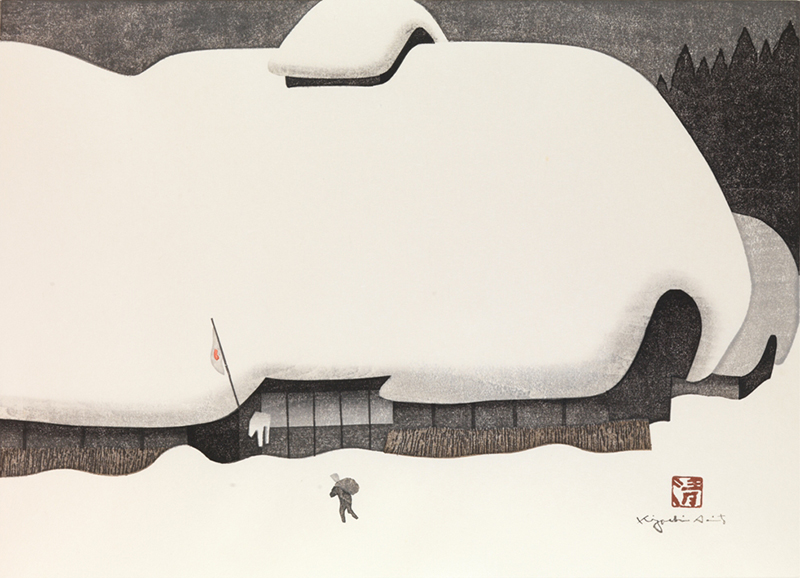

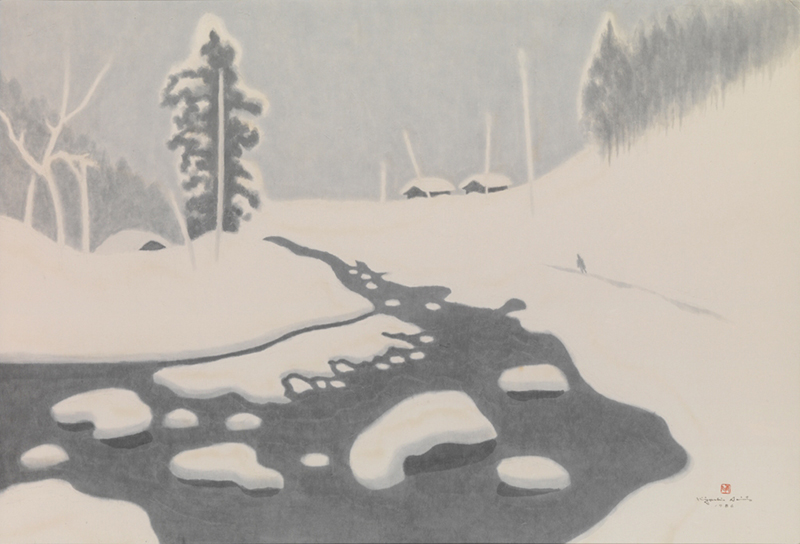

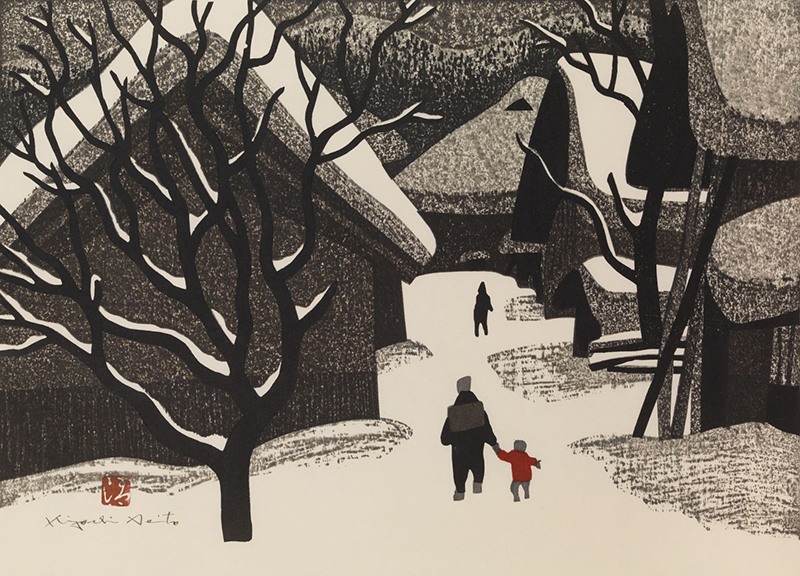

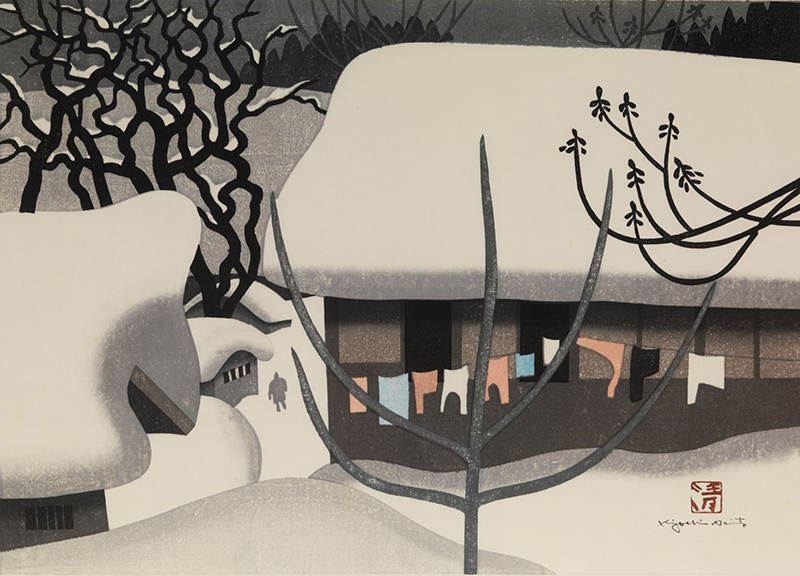

Kiyoshi Saito started out as a sign maker and studied on his own before jumping into the world of painting. His life’s path was determined when he accidently encountered woodblock prints by Sotaro Yasui. He began the Winter in Aizu series during this time, a theme he continued depicting for the rest of his life.

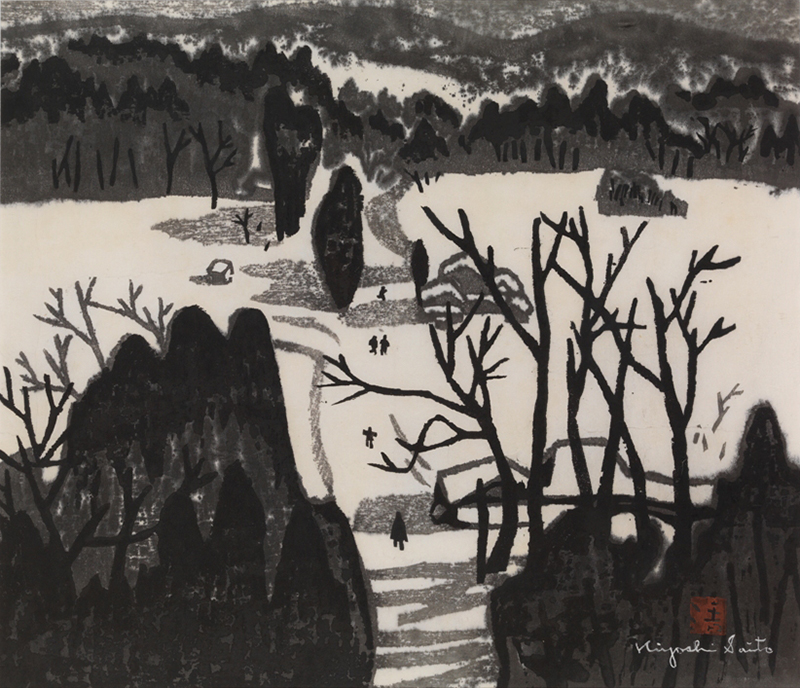

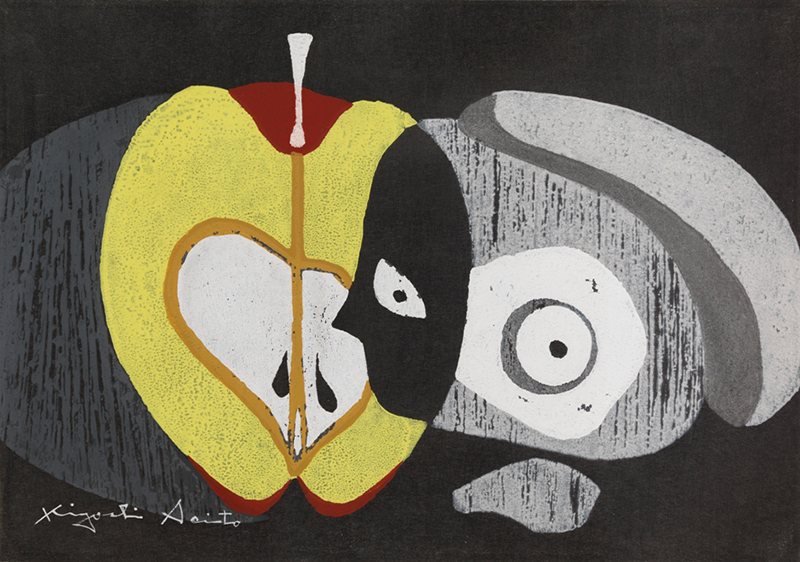

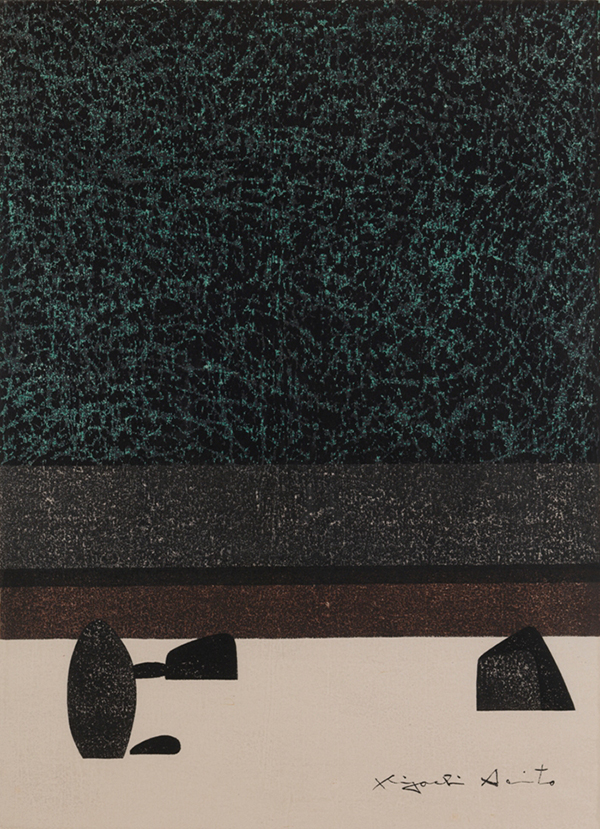

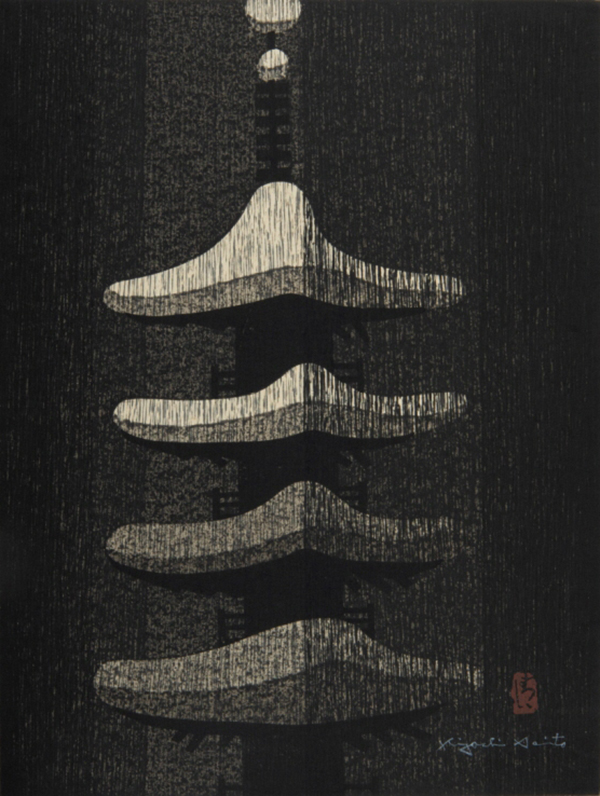

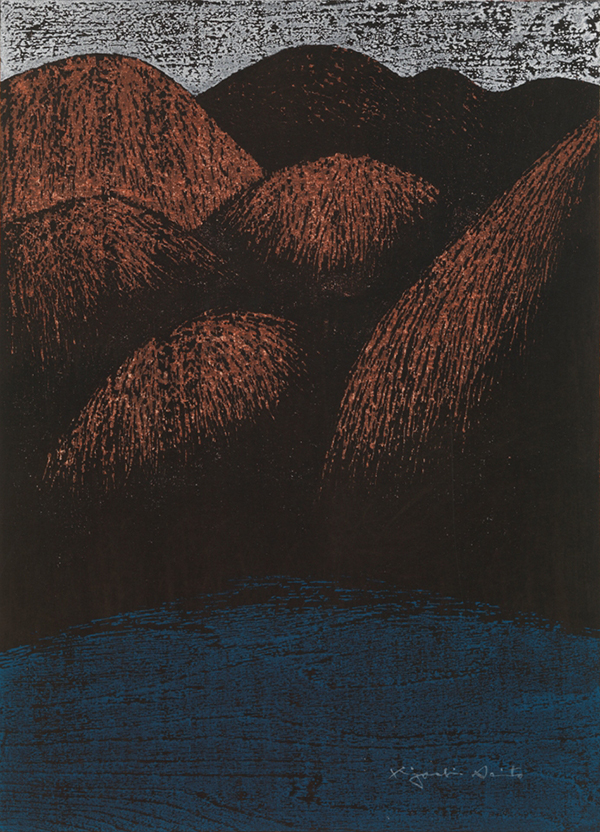

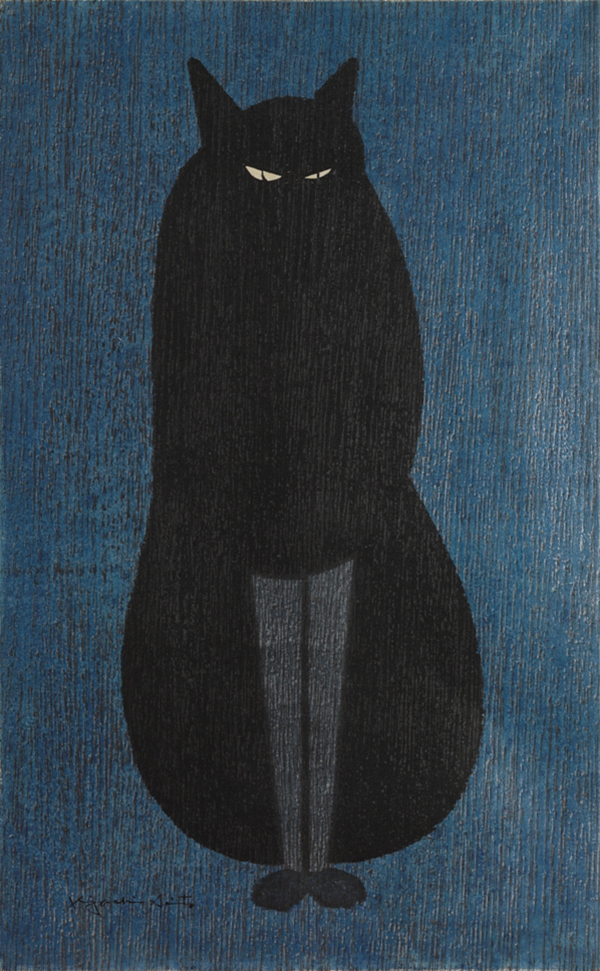

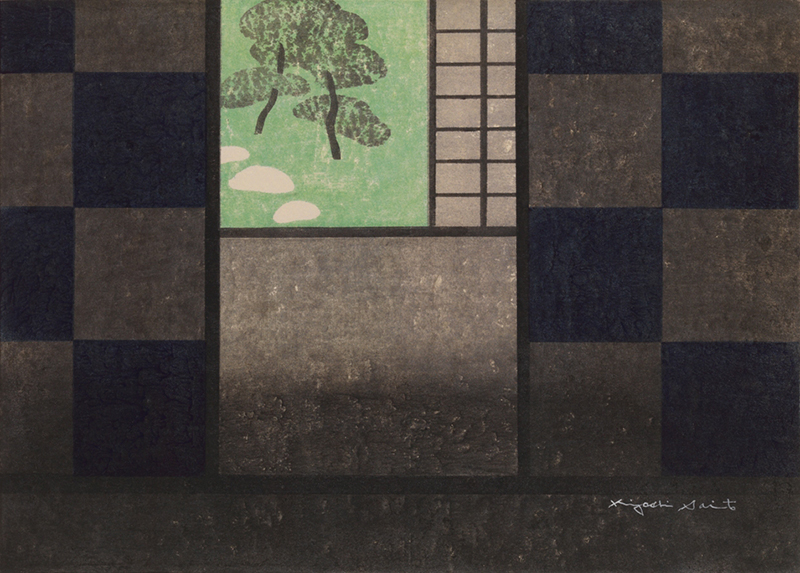

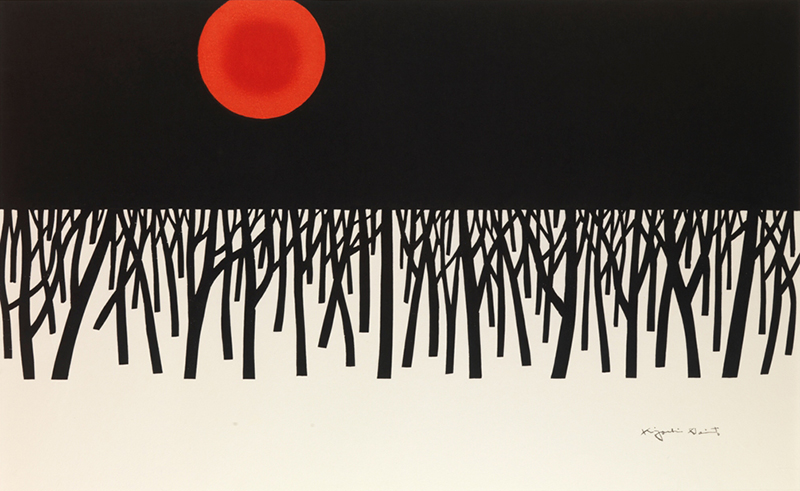

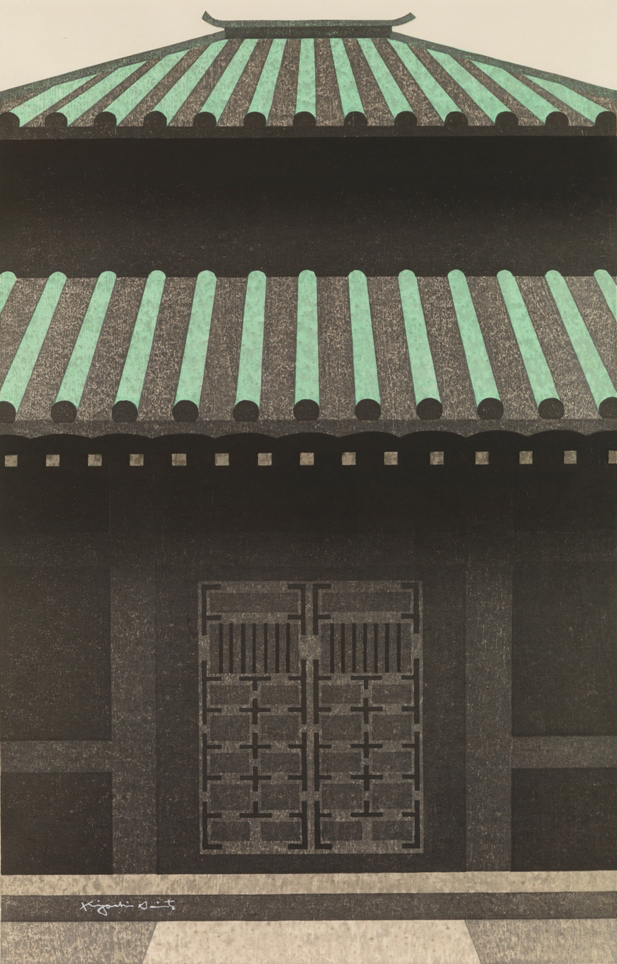

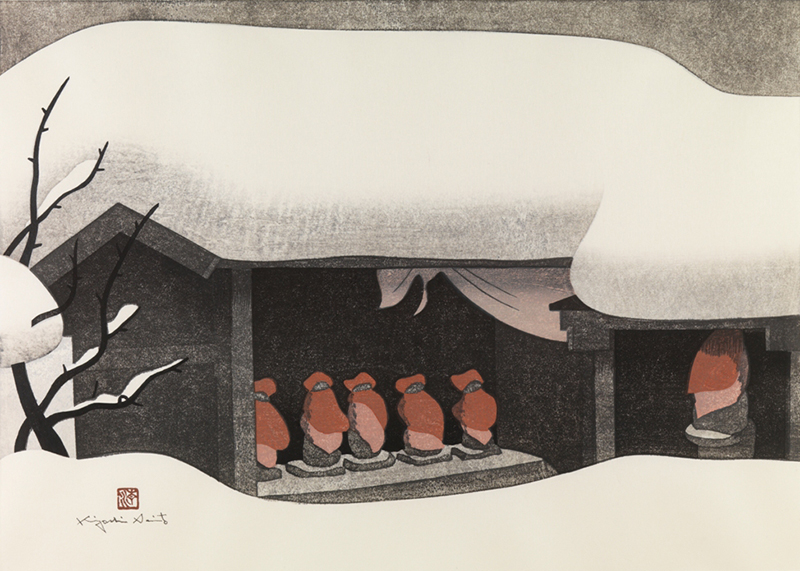

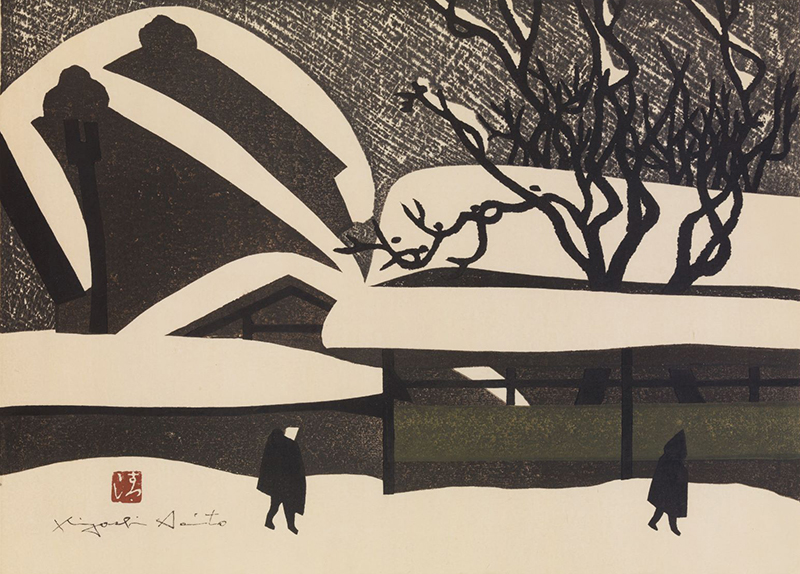

- Stone Garden

- 1955

Woodblock print on paper

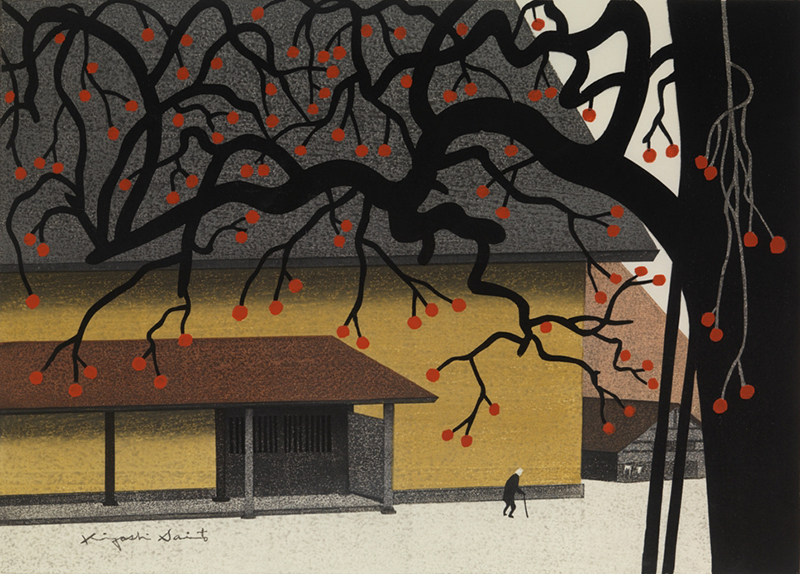

Saito gains

worldwide renown

- “I think Gauguin’s influence is why my pictures became flat”

- “I was mesmerized by the extremely simple composition of Ryoan-ji temple’s stone garden”

Saito responded to the work of Gauguin, Munch, and Redon, and turned his attention to the forms of clay figurines, Buddhist statues, stone gardens, and ancient architecture, combining the essence of modern Western painting with the aesthetic of traditional Japanese culture. His refined forms and compositions with vividly colored, flat areas of color brought Saito acclaim across the globe.

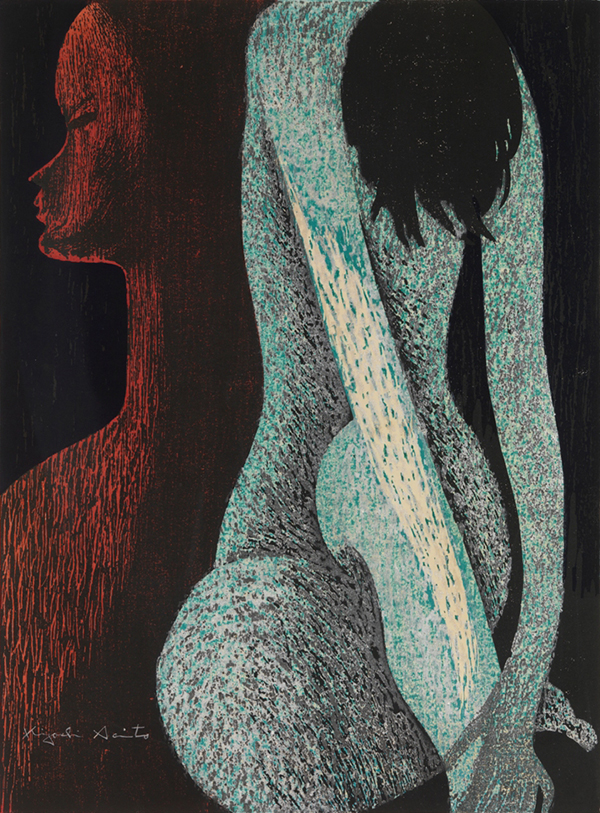

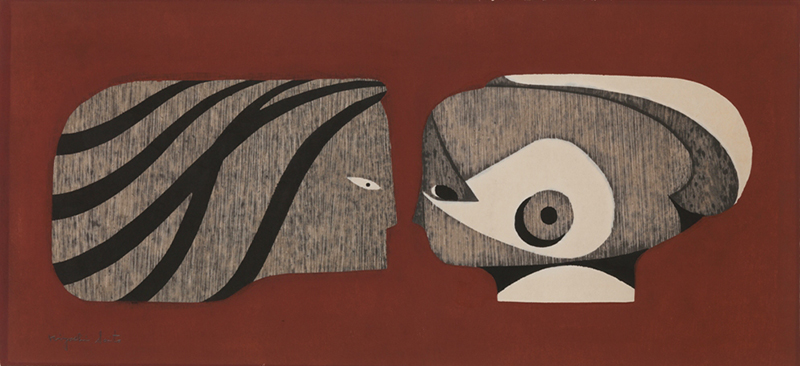

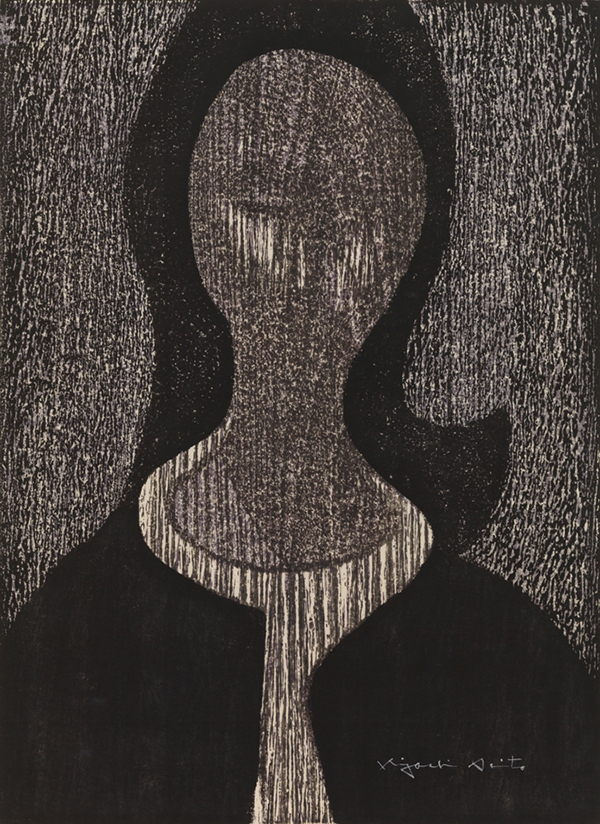

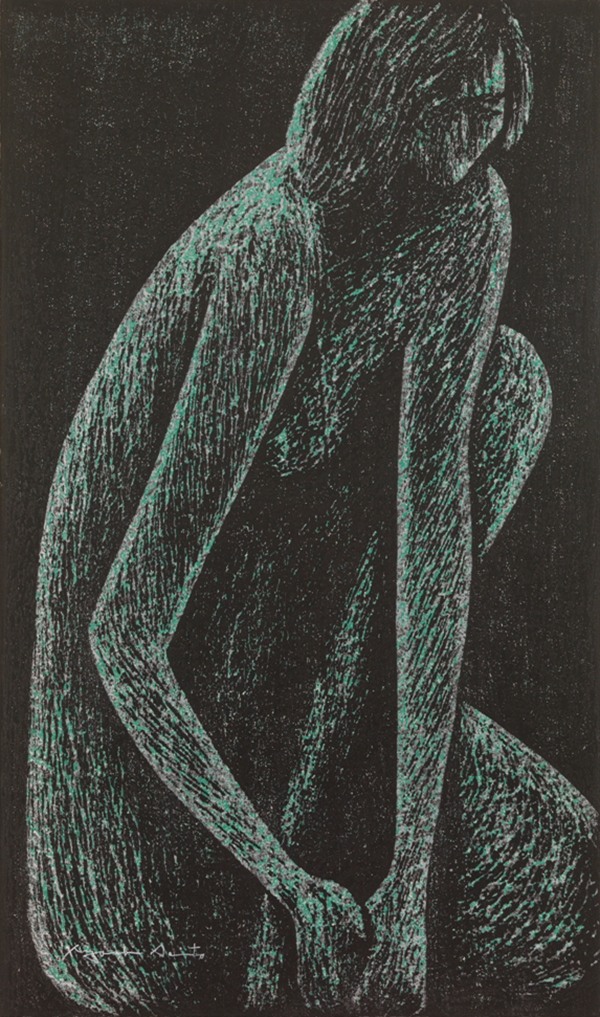

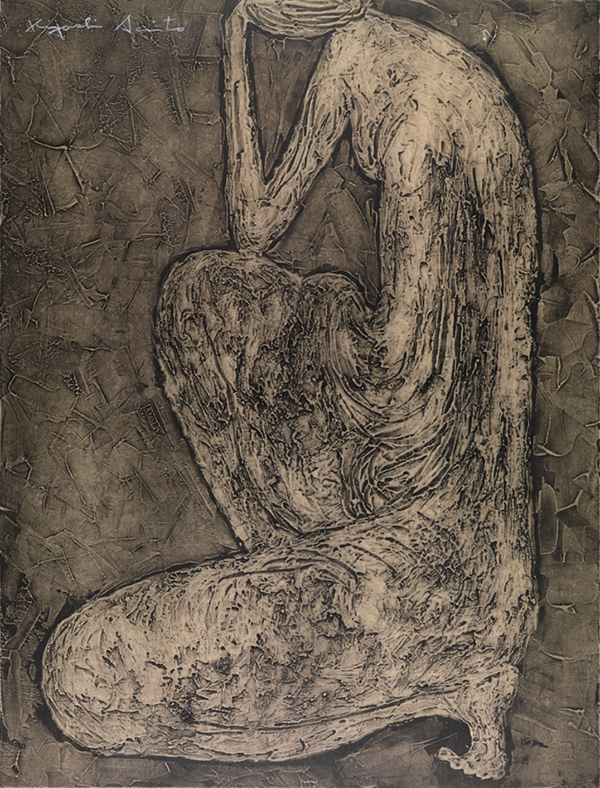

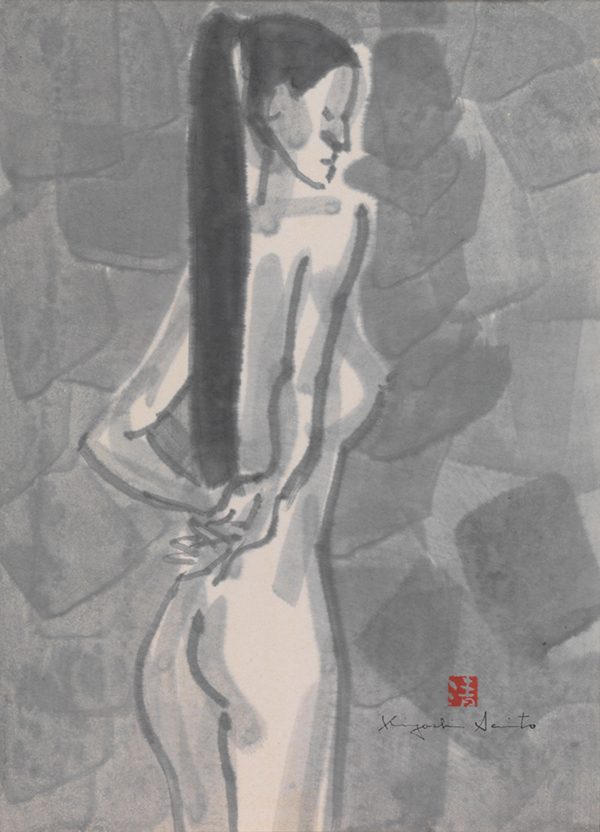

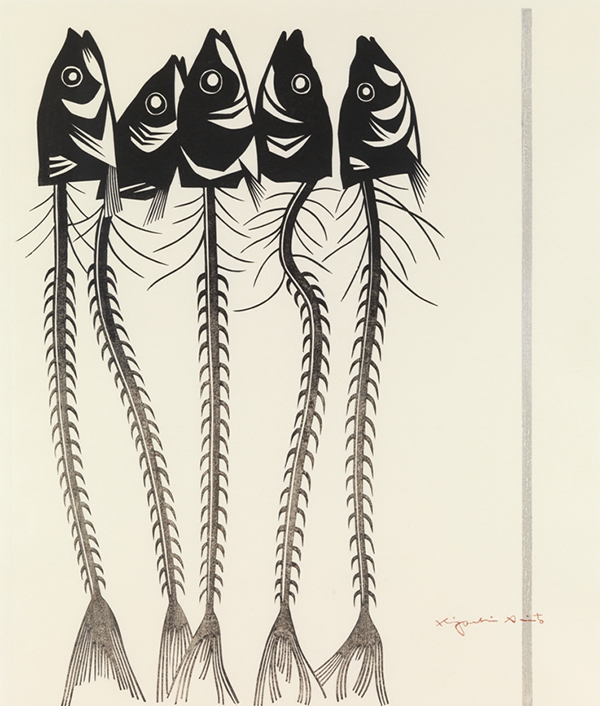

- Nude (G)

- 1966

Woodblock print on paper

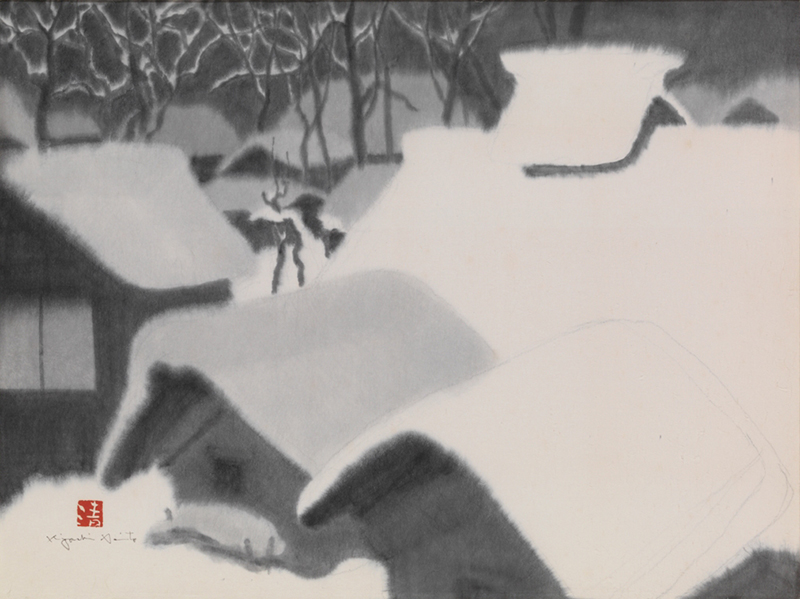

Suffering and abundance

- “I started worrying what would happen if I kept drawing things like this, and I suddenly lost the ability to draw”

- “I was sketching the face of my maid when the fuzzy lines of my youth appeared. I was taken aback.”

Despite his growing acclaim and popularity, Saito struggled to figure out which direction he should proceed. Unlike the work he did in the 1950s, he began filling his flat areas of color with woodgrain and goma-zuri patterns, and also tried out collagraph and bokuga (sumi ink painting) techniques he had never used before. As his work grew more expressive, he discovered shadows—something that should have been removed in his previous process of flattening and simplification. This was a turning point for Saito.

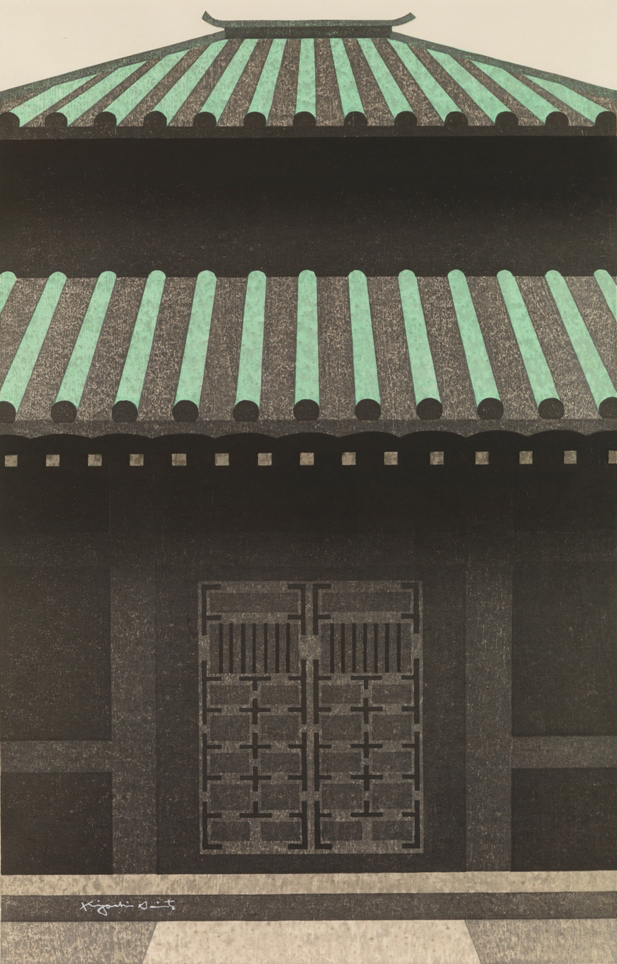

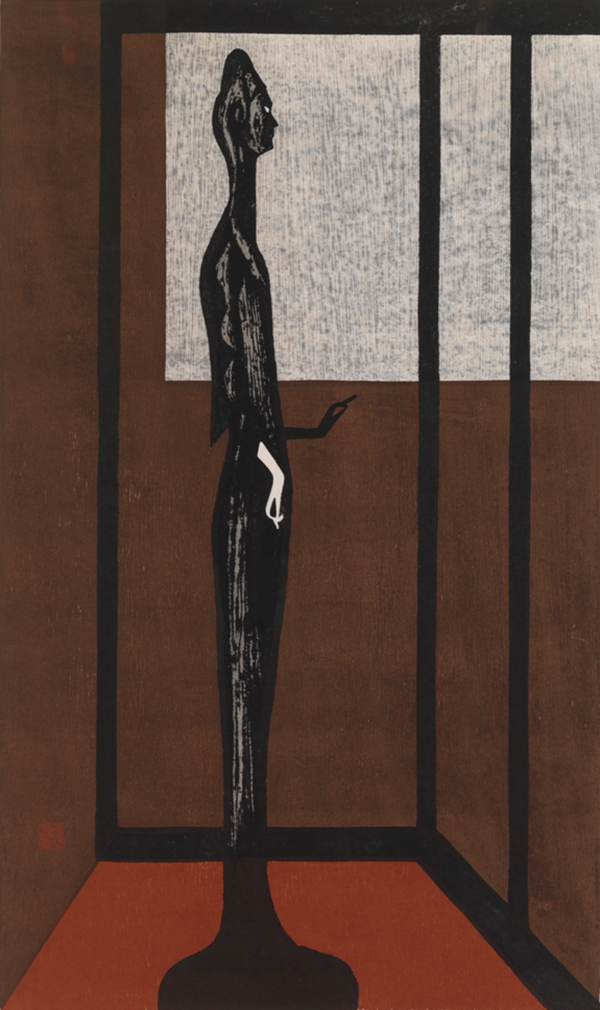

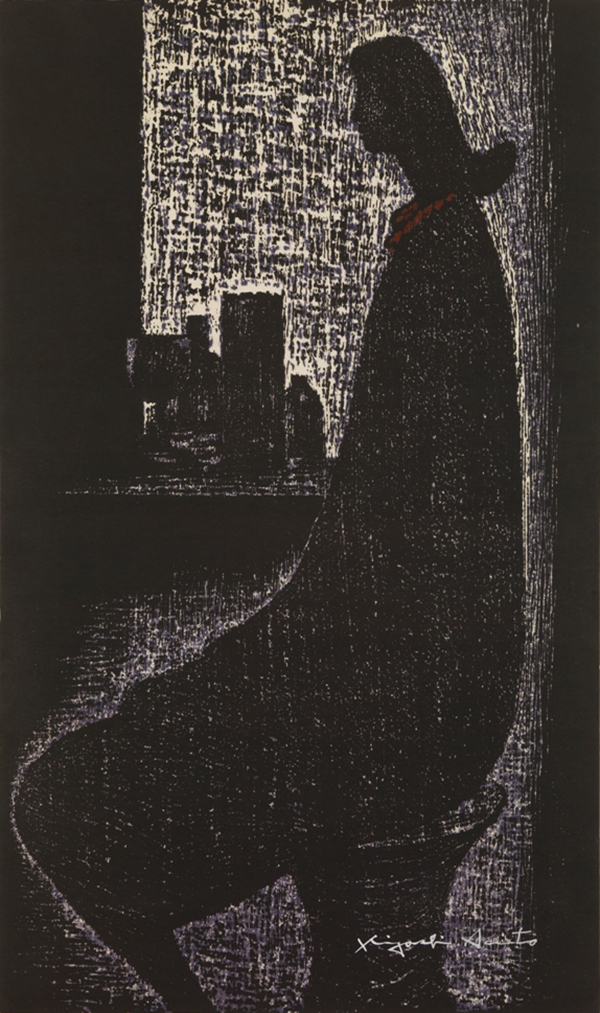

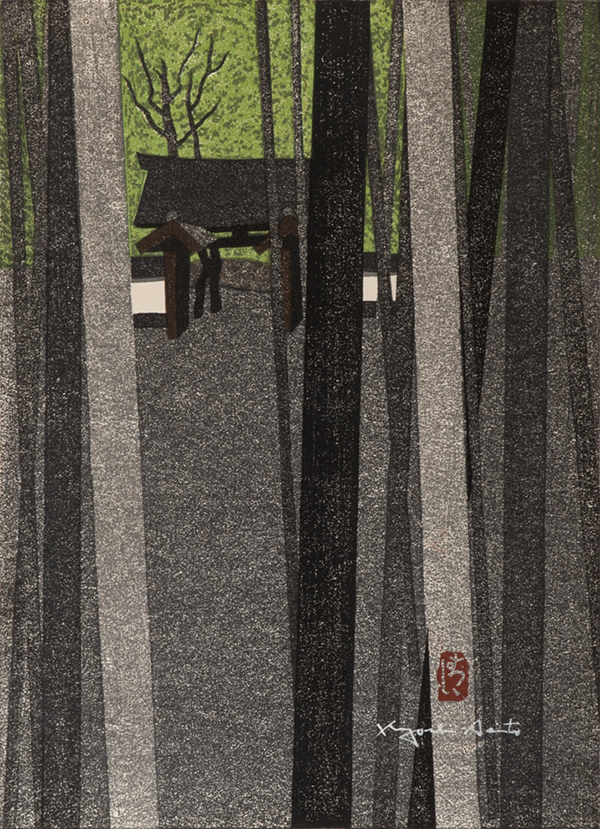

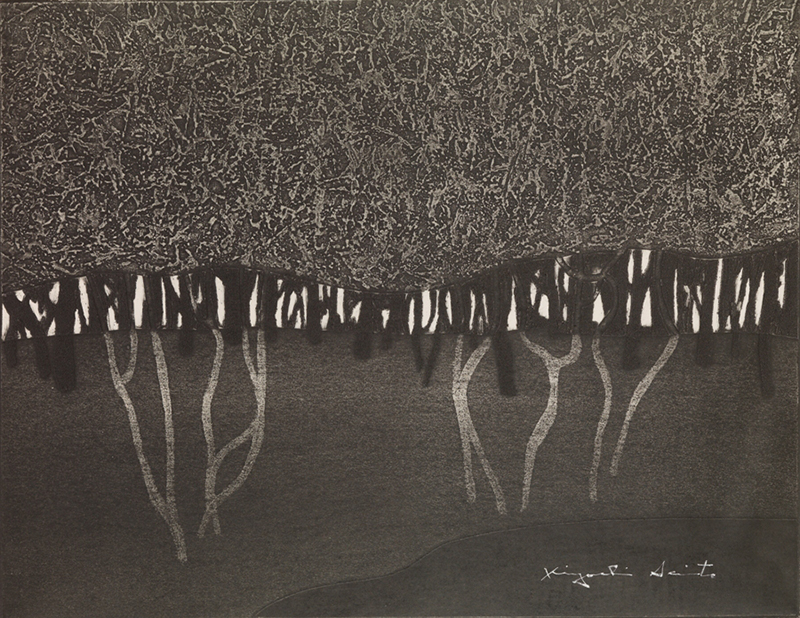

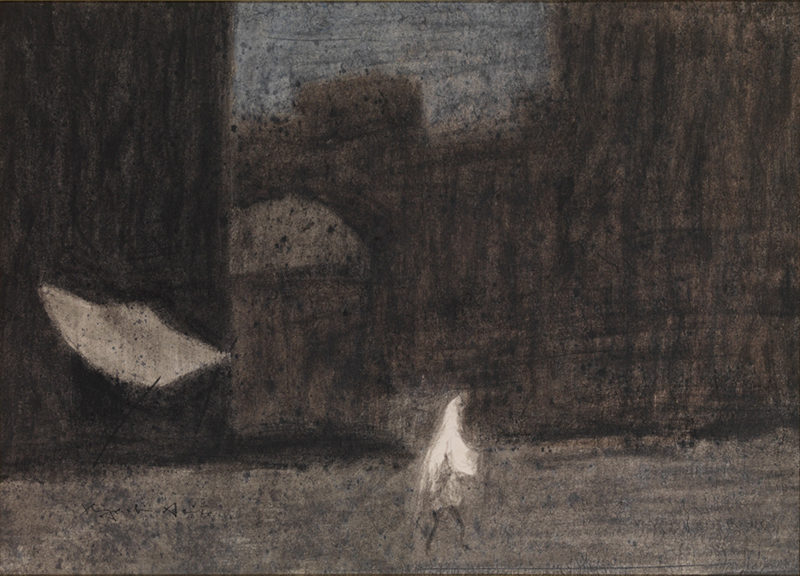

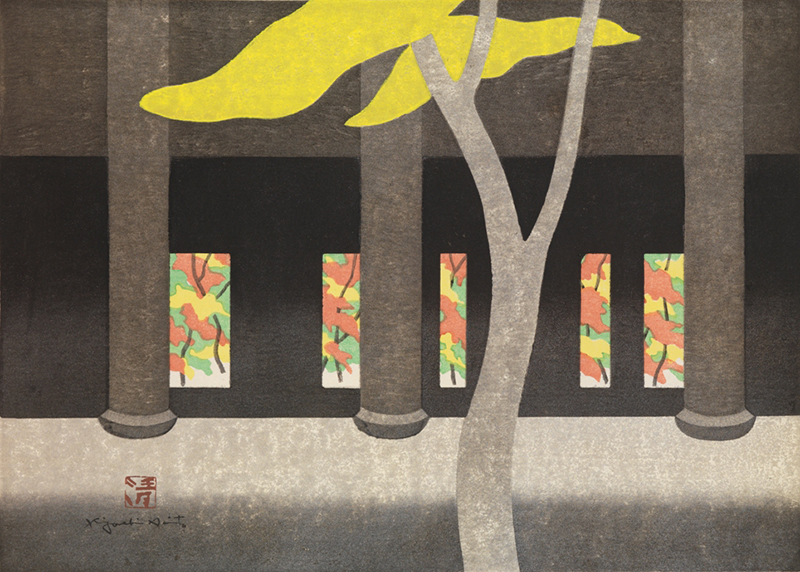

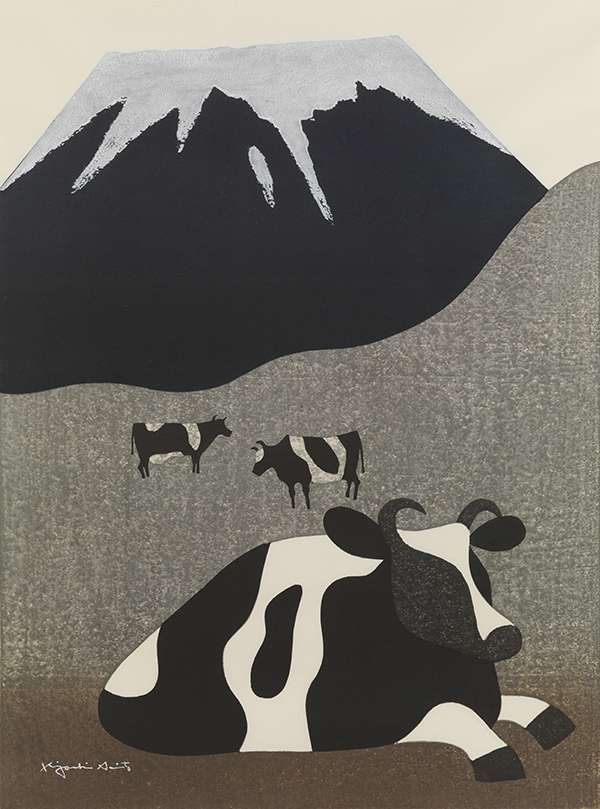

- Door, Eisho-ji Temple, Kamakura

- 1984

Woodblock print on paper

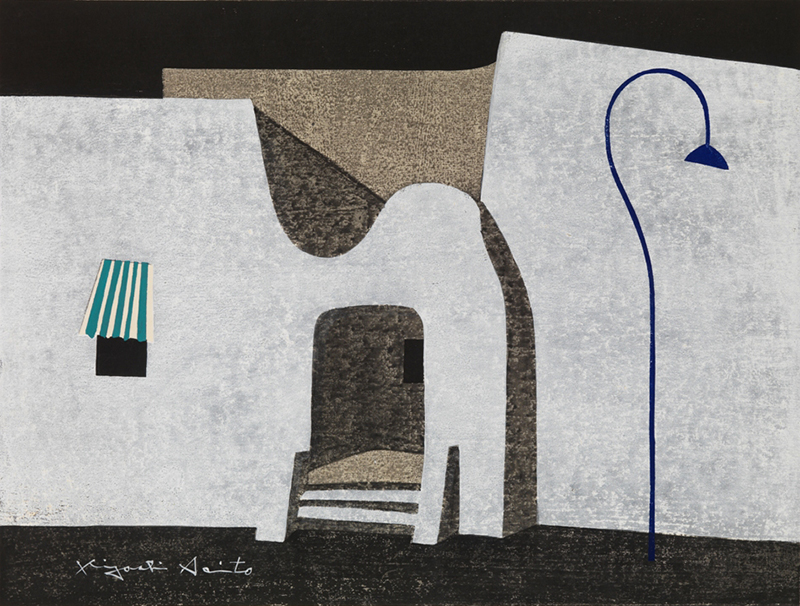

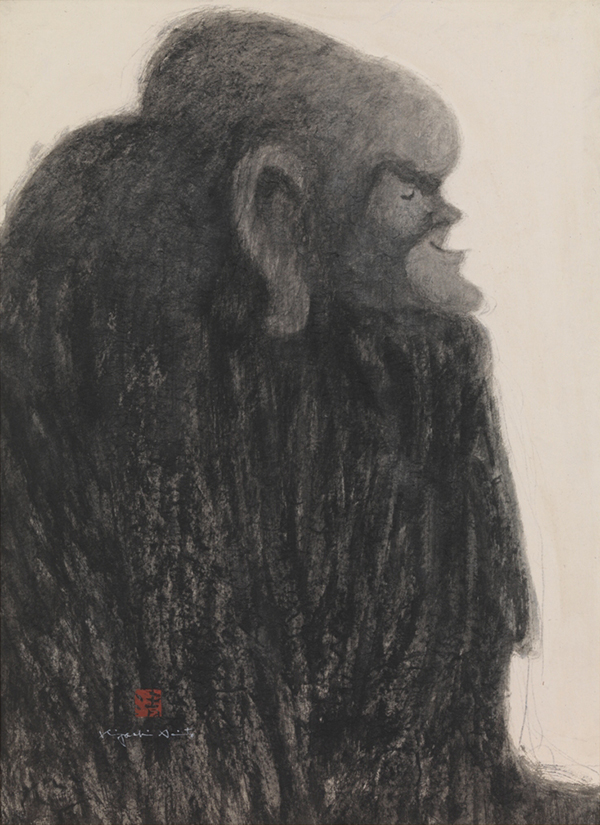

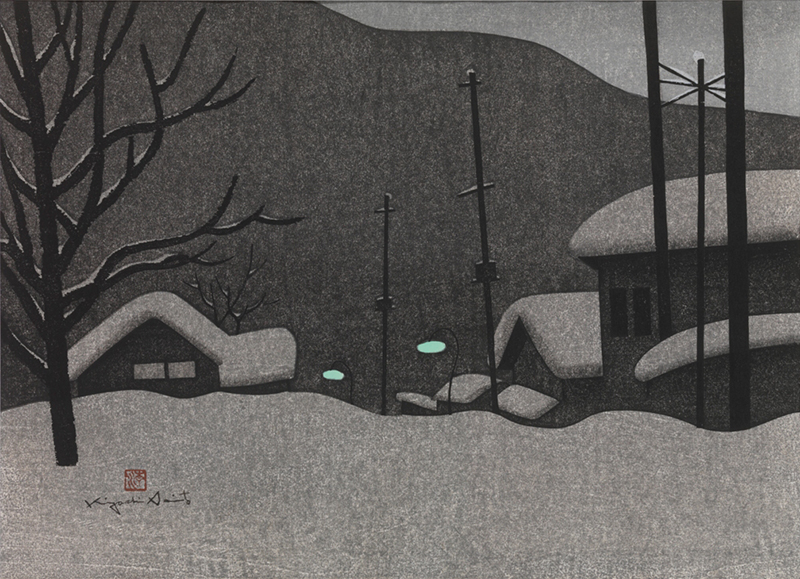

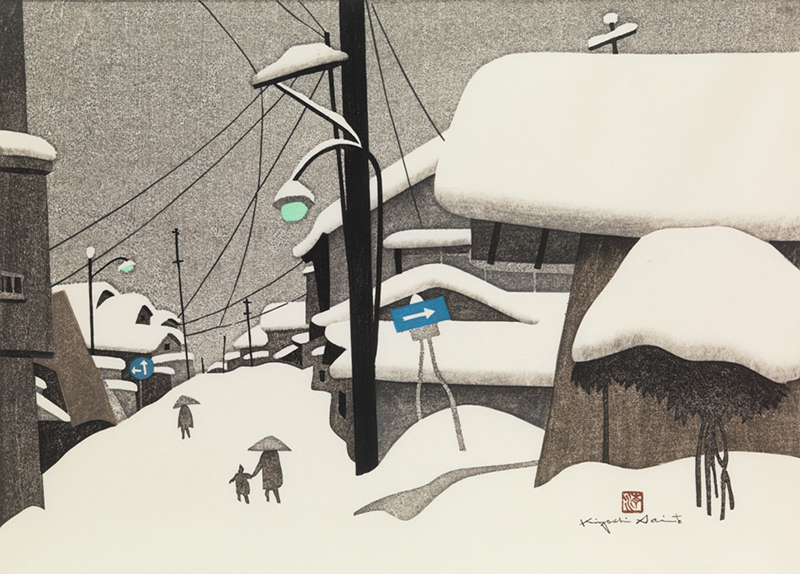

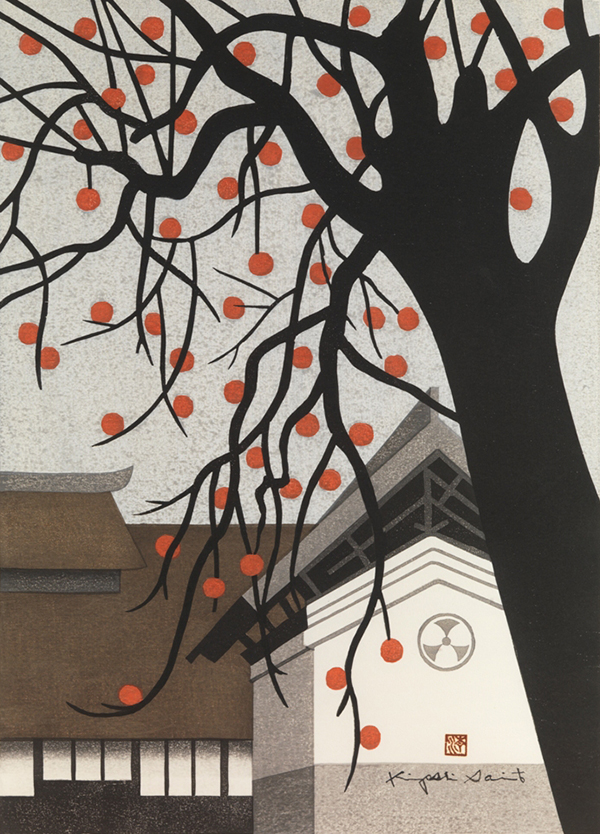

The birth of shadows:

Saito’s return and greater depth

- “I didn’t start drawing Aizu’s winter scenery out of homesickness—it was a matter of composition”

- “I struggled to find my own compositions in my work from Kamakura”

Shadows brought greater depth and presence to Saito’s work, and he once again took up the themes he worked on during the 1950s. His compositions and forms were further refined, and his skillfully gradated shadows breathed a profound spirituality into his work. He also began working on new series. One important subject was Kamakura, where he moved in 1970. He also started the 115-piece Winter in Aizu series. In this way, Saito’s work gained greater depth and range.

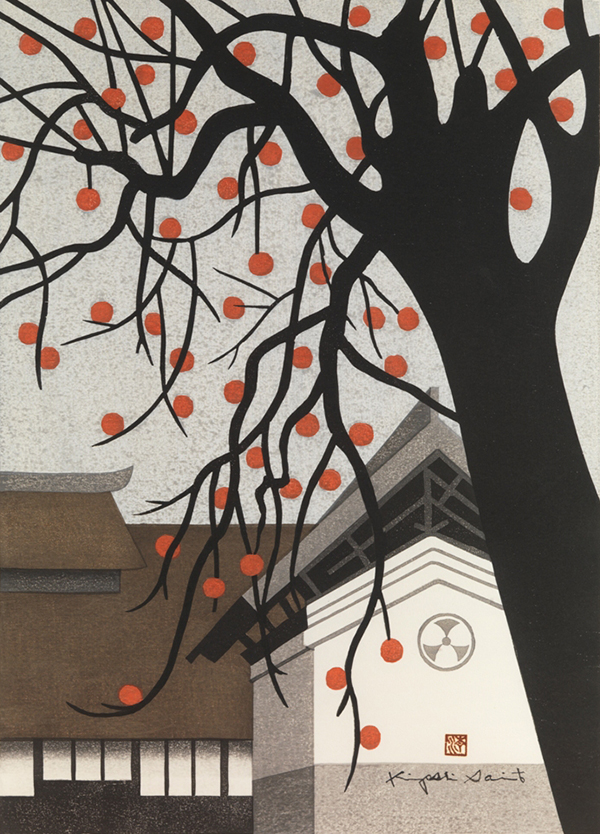

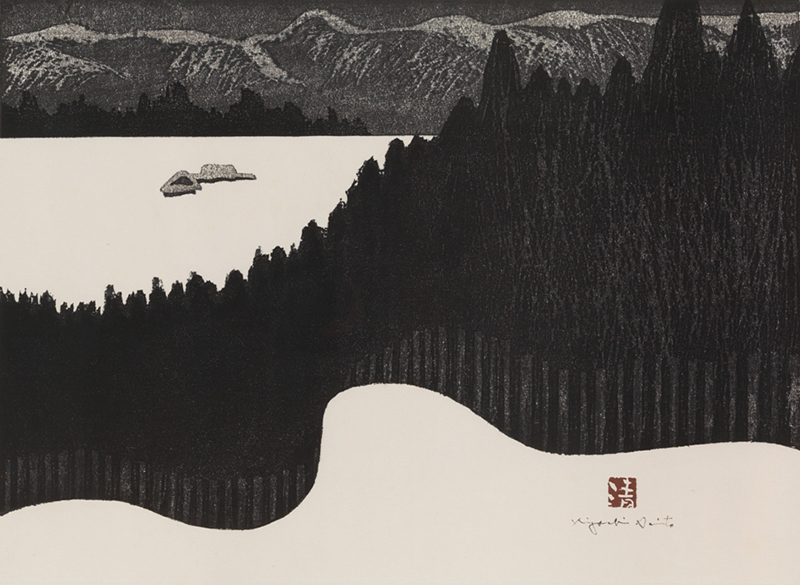

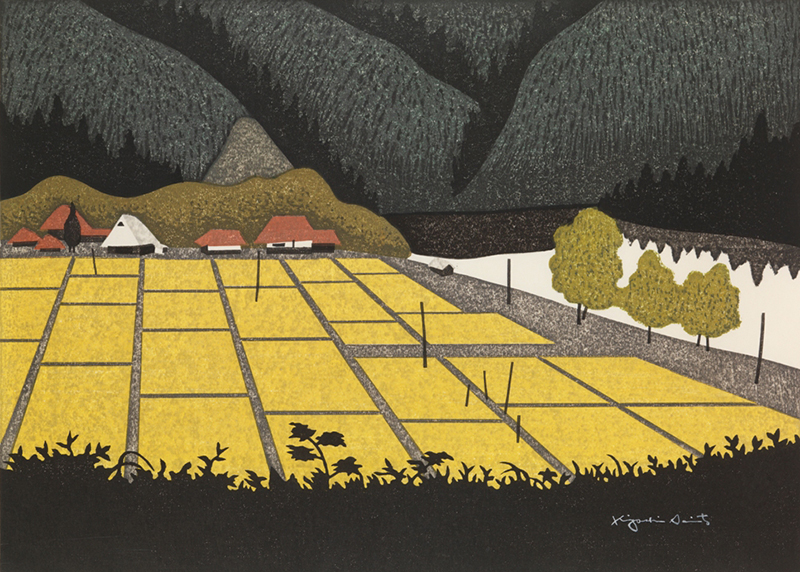

- Persimmon Tree in Aizu (38)

- 1996

Woodblock print on paper

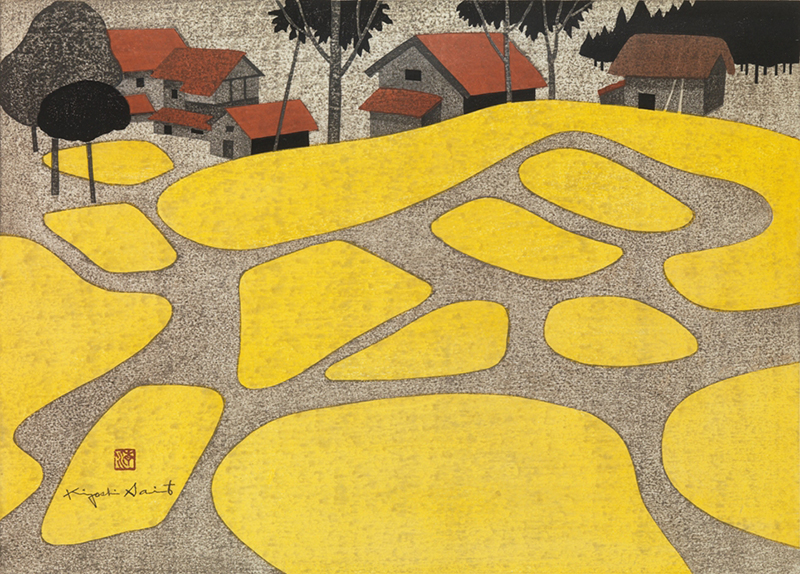

Saito’s Aizu:

affection and grandeur

- “Somehow it seemed like my own hometown.

Somehow I still felt like a stranger in the bottom of my heart.” - “Maybe these images are so sad because I learned how hard it is to live with snow”

Saito left Aizu as a young boy but had never lived there again, although he visited multiple times. He moved from Kamakura to Yanaizu (in the Aizu region) in 1987, where he spent the final decade of his life. Despite his age, he watched and repeatedly sketched the terrain and its residents. His initial interest as an artist was the compositions and forms in a landscape. But as his expressiveness gained greater depth, these transformed into depictions revealing the complex emotions he had about his birthplace. Saito felt like a stranger in Aizu, yet he continued drawing the area until the end of his life. He made nostalgic landscapes that evoke a sense of longing for home in the viewer.

- Dresser

- 1930s – 1940s

Woodblock print on paper

- Woman in My Native Village

- 1937

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (Bange)

- Around 1940

Woodblock print on paper

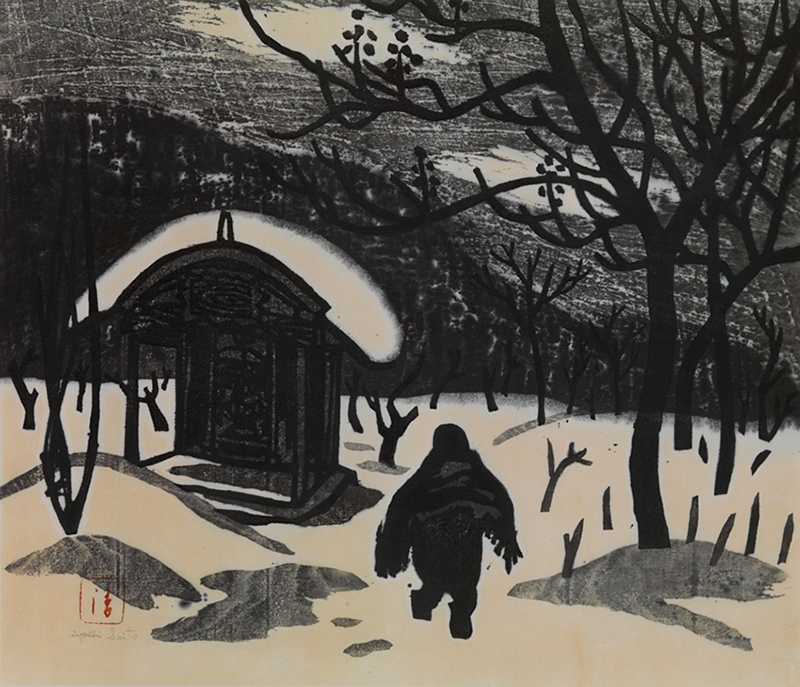

- Winter in Aizu, Gobo-do

- 1940

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu, Kubo

- Around 1940

Woodblock print on paper

- Asakusa Scene

- 1945

Woodblock print on paper

- Woman in Fishing Village

- 1946

Woodblock print on paper

- Camellia

- 1945

Oil paint on canvas

- Resting

- 1946

Oil paint on board

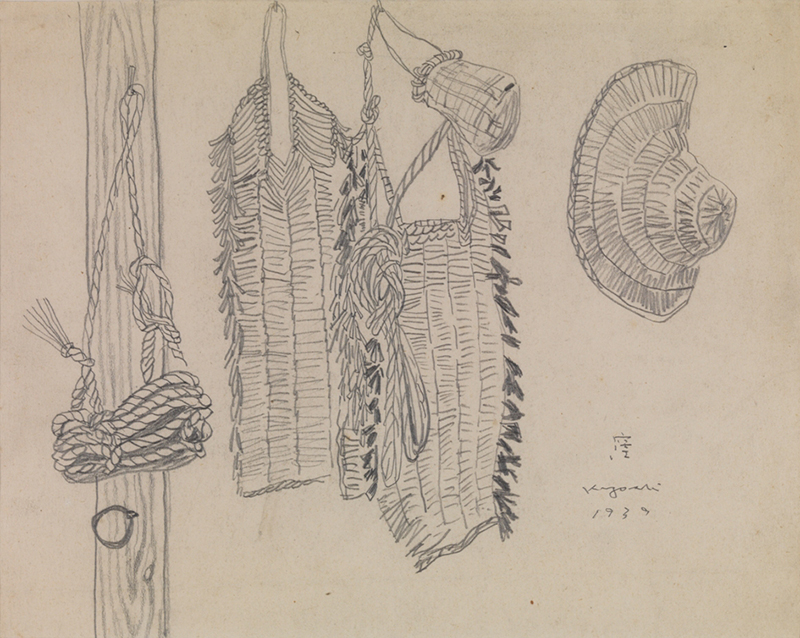

- Children in Aizu (6)

- 1939

Pencil on paper

- Children in Aizu (43)

- 1939

Pencil on paper

- Venus

- 1947

Woodblock print on paper

- Solitude

- 1947

Woodblock print on paper

- Steady Gaze

- 1948

Woodblock print on paper

- Red Flower

- 1948

Woodblock print on paper

- Milk

- 1949

Woodblock print on paper

- Naoko

- 1949

Woodblock print on paper

- Steady Gaze

- 1950

Woodblock print on paper

- Nude (A)

- 1950

Woodblock print on paper

- Nude (B)

- 1950

Woodblock print on paper

- Miroku-Bosatsu Bodhisattva

- 1950

Woodblock print on paper

- Steady Gaze

- 1952

Woodblock print on paper

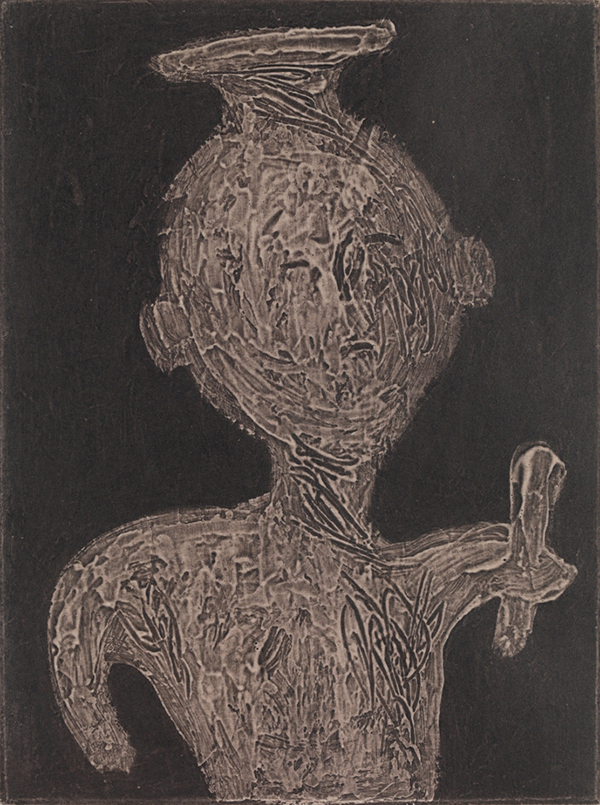

- Clay Figurine and Earthenware (J)

- 1952

Woodblock print on paper

- Clay Figurine

- 1953

Woodblock print on paper

- Clay Figurine

- 1954

Woodblock print on paper

- Asuka

- 1954

Woodblock print on paper

- Stone Garden

- 1955

Woodblock print on paper

- Katsura, Kyoto

- 1955

Woodblock print on paper

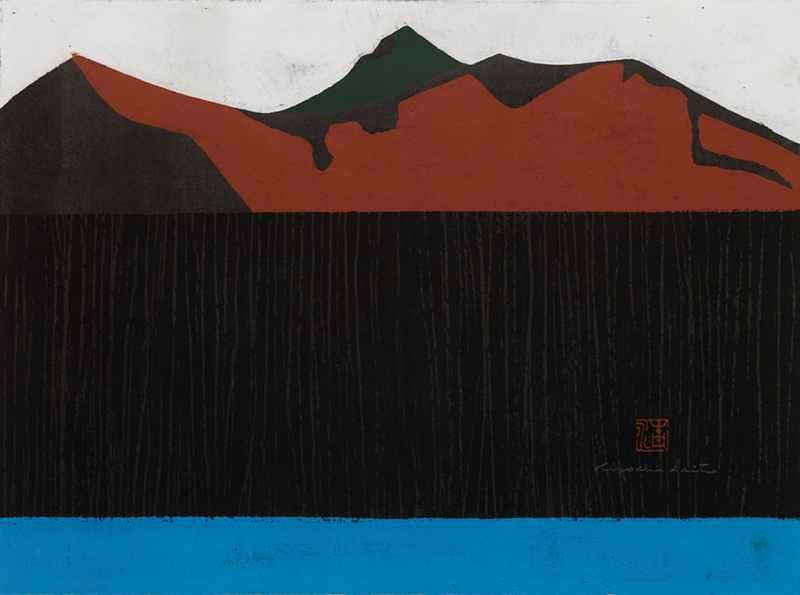

- Ura-Bandai, Aizu

- 1955

Woodblock print on paper

- Blue Marsh, Ura-Bandai

- 1955

Woodblock print on paper

- Coral

- 1955

Woodblock print on paper

- Rain in Ann Arbor, Michigan

- 1956

Woodblock print on paper

- Shrine (A)

- 1959

Woodblock print on paper

- Wall of Kyoto (A)

- 1960

Woodblock print on paper

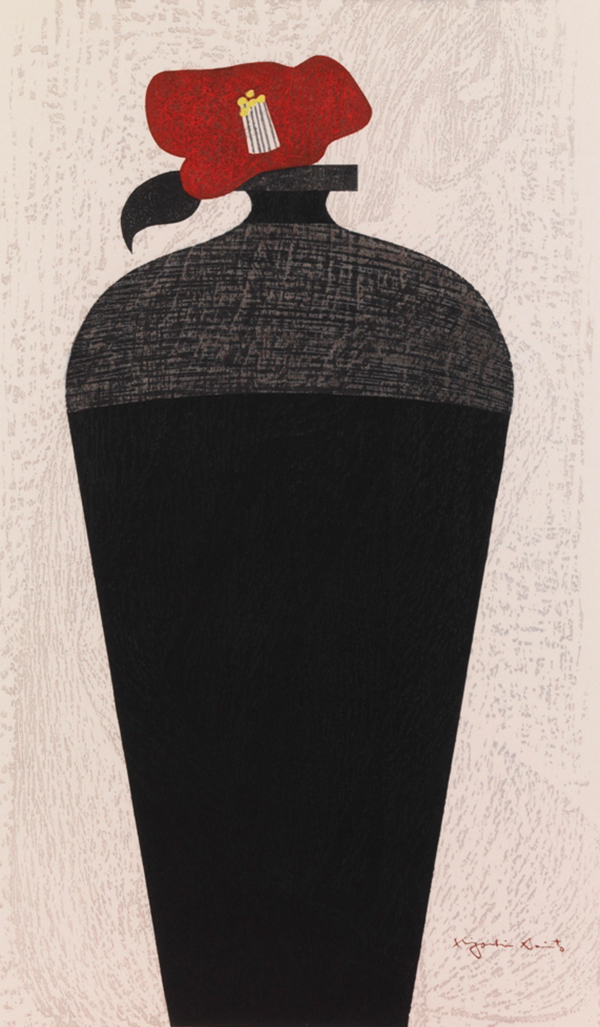

- Maiko, Kyoto (H)

- 1961

Woodblock print on paper

- Steady Gaze

- 1962

Woodblock print on paper

- Rain, Paris (B)

- 1962

Woodblock print on paper

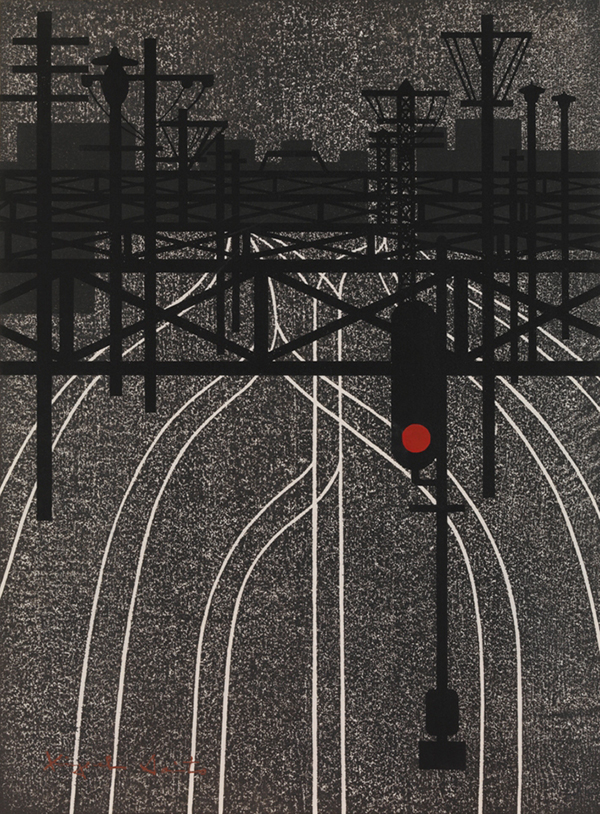

- Signal (A)

- 1962

Woodblock print on paper

- New Mexico

- 1965

Woodblock print on paper

- Stone Garden (C)

- 1965

Woodblock print on paper

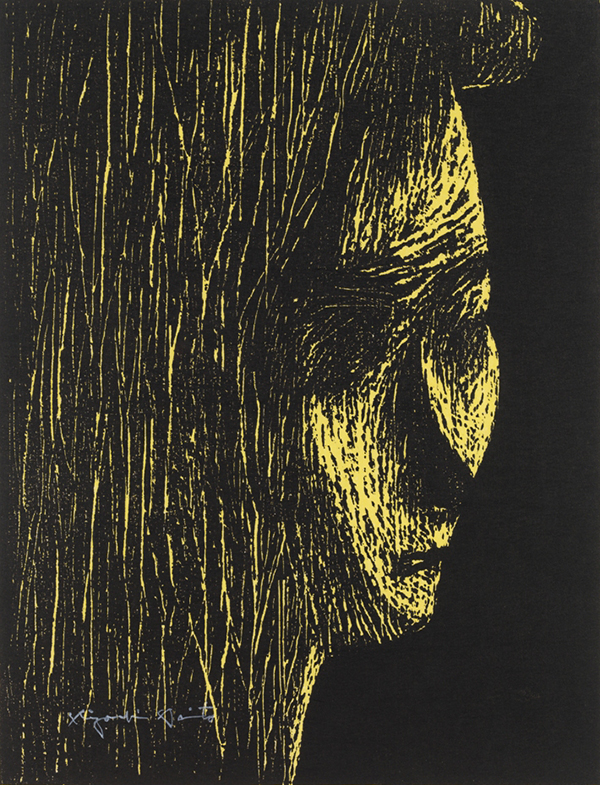

- Face

- 1966

Woodblock print on paper

- Naoko

- 1966

Woodblock print on paper

- Resting

- 1966

Woodblock print on paper

- Nude (G)

- 1966

Woodblock print on paper

- Recollection

- 1967

Woodblock print on paper

- Autumn

- 1967

Woodblock print on paper

- India (C)

- 1968

Woodblock print on paper

- Muro-ji Temple in Snow, Nara

- 1968

Woodblock print on paper

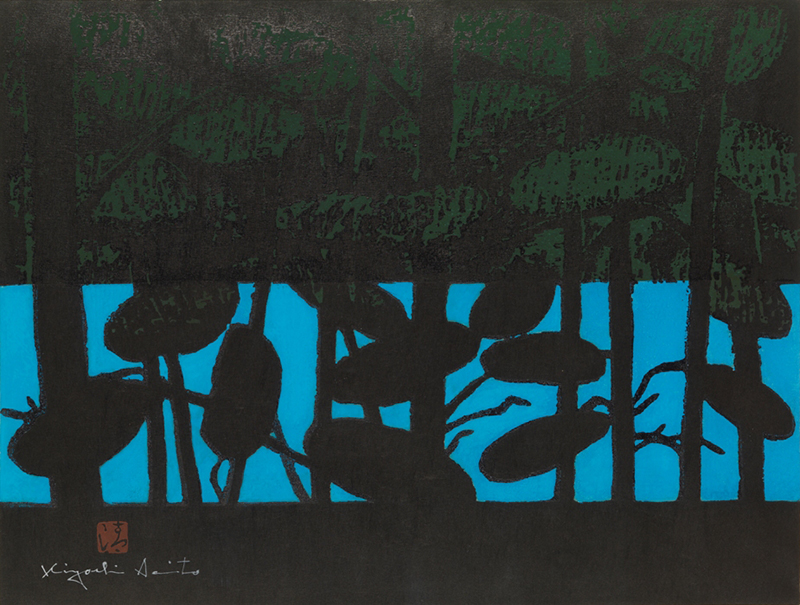

- Jizo-in Temple, Eryuzan, Kyoto

- 1968

Woodblock print on paper

- Autumn in Aizu (B)

- 1969

Woodblock print on paper

- Greenwich Village

- 1962

Collagraph on paper

- Twanoh State Park

- 1962

Collagraph on paper

- Banyan Tree, Hawaii (F)

- 1964

Collagraph on paper

- Nude (5)

- 1963

Collagraph on paper

- Clay Figurine (F)

- 1968

Collagraph on paper

- One Afternoon

- 1968

Collagraph on paper

- Nude

- 1969

Sumi ink on paper

- India

- 1967

Sumi ink and color on paper

- Winter at Hokke-do Temple, Nikko

- 1969

Sumi ink and color on paper

- Winter in Aizu (1) Kubo

- 1970

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (23) Yanaizu

- 1976

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (35) Yagisawa

- 1978

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (57) Inawashiro

- 1982

Woodblock print on paper

- Steady Gaze

- 1971

Woodblock print on paper

- Tahiti (C)

- 1971

Woodblock print on paper

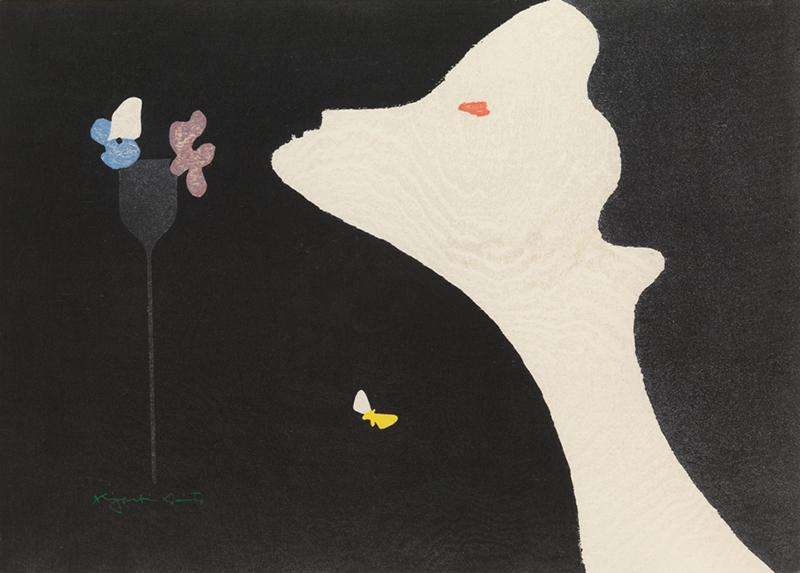

- Flower and a Girl (5)

- 1971

Woodblock print on paper

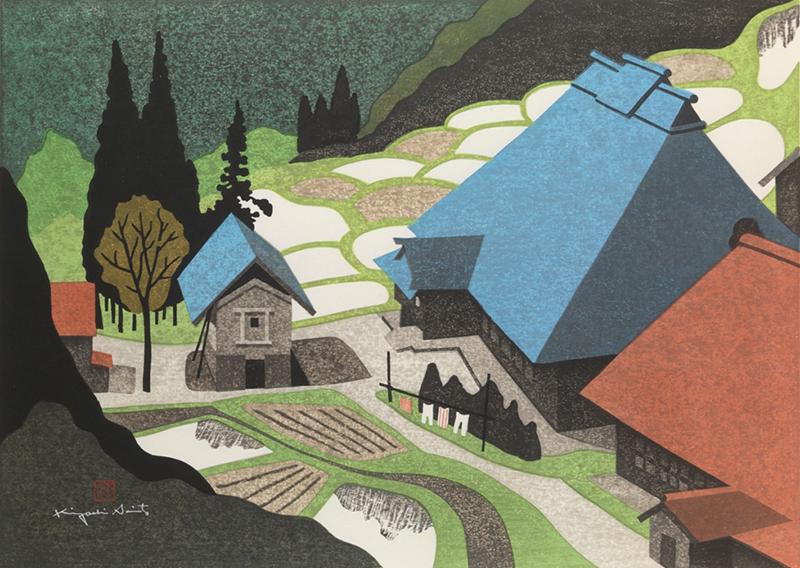

- House in Aizu (A)

- 1972

Woodblock print on paper

- Gate, Kamakura (E)

- 1972

Woodblock print on paper

- June, Kamakura (C)

- 1972

Woodblock print on paper

- Persimmon Tree in Aizu (3)

- 1973

Woodblock print on paper

- Persimmon Tree in Aizu (11)

- 1975

Woodblock print on paper

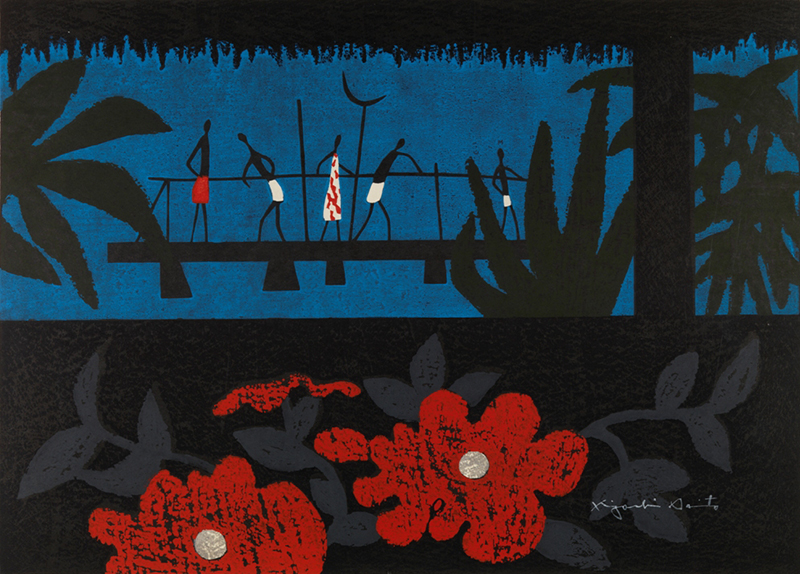

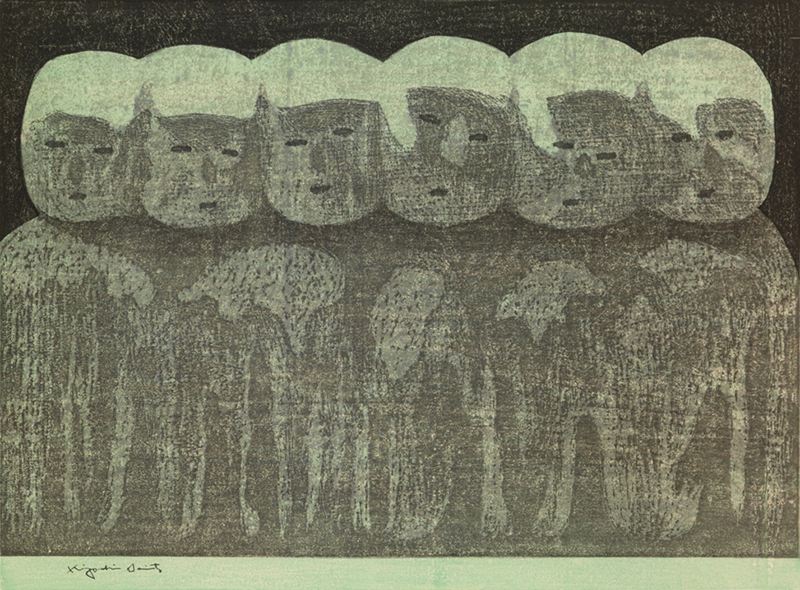

- Beauty Contest

- 1973

Woodblock print on paper

- Associates (B)

- 1974

Woodblock print on paper

- Katsura, Kyoto

- 1974

Woodblock print on paper

- Gate, Nanzen-ji Temple, Kyoto

- 1974

Woodblock print on paper

- Notre-Dame, Paris

- 1974

Woodblock print on paper

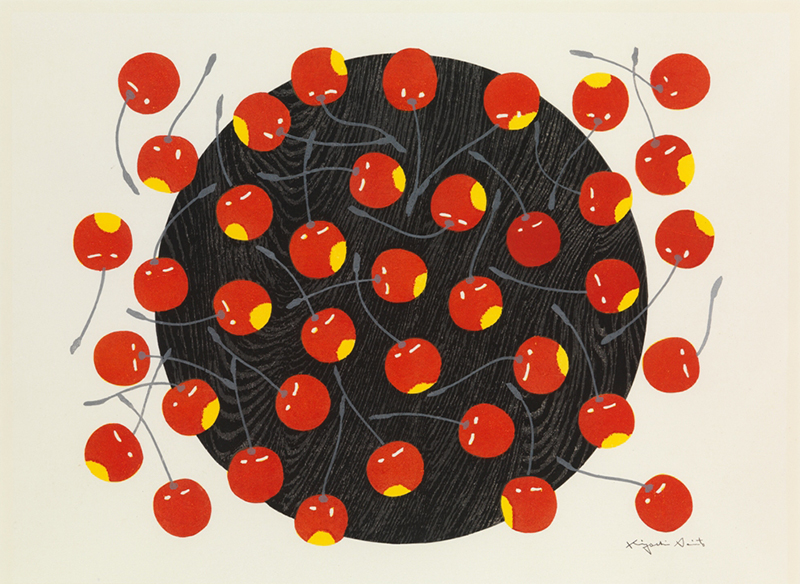

- Cherry

- 1974

Woodblock print on paper

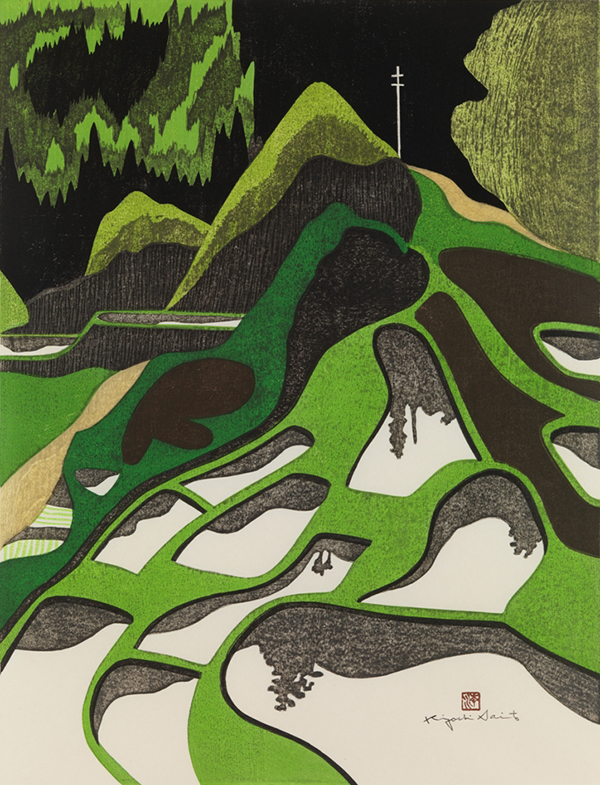

- The Harvest Season in Aizu (2)

- 1975

Woodblock print on paper

- The Harvest Season in Aizu (7)

- 1983

Woodblock print on paper

- Tenderness

- 1975

Woodblock print on paper

- Snow, Sunset

- 1975

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Paris

- 1975

Woodblock print on paper

- The Eye (5)

- 1975

Woodblock print on paper

- Tadami River, Aizu Yanaizu (1)

- 1979

Woodblock print on paper

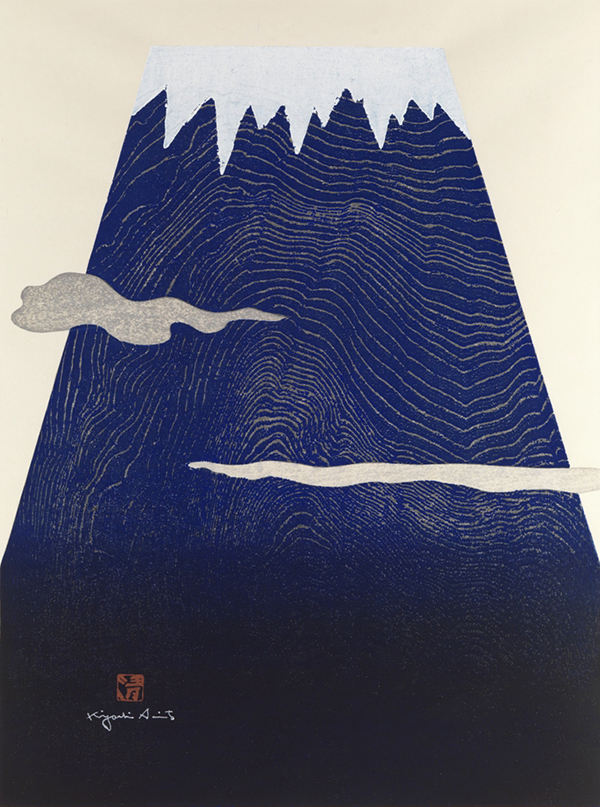

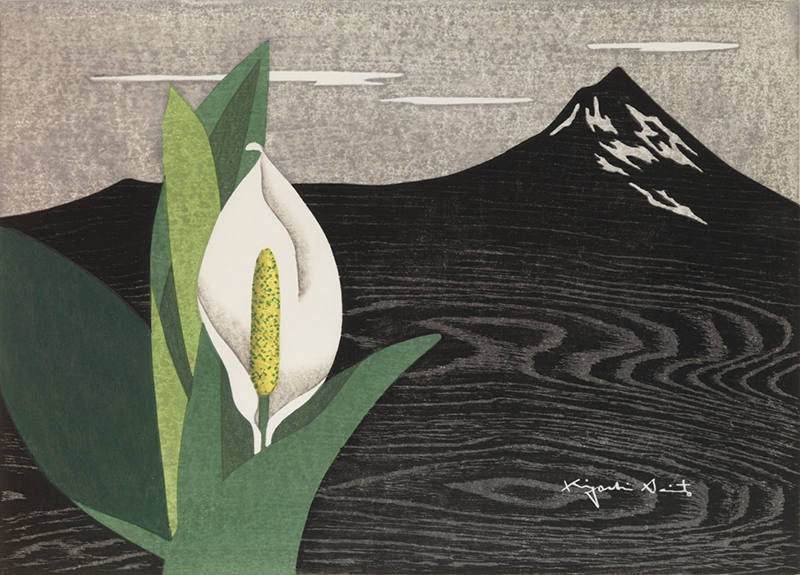

- Mt. Fuji (4) Ranch (B)

- 1980

Woodblock print on paper

- Mt. Fuji (15) Fine Weather

- 1980

Woodblock print on paper

- Afterglow, Kamakura

- 1979

Woodblock print on paper

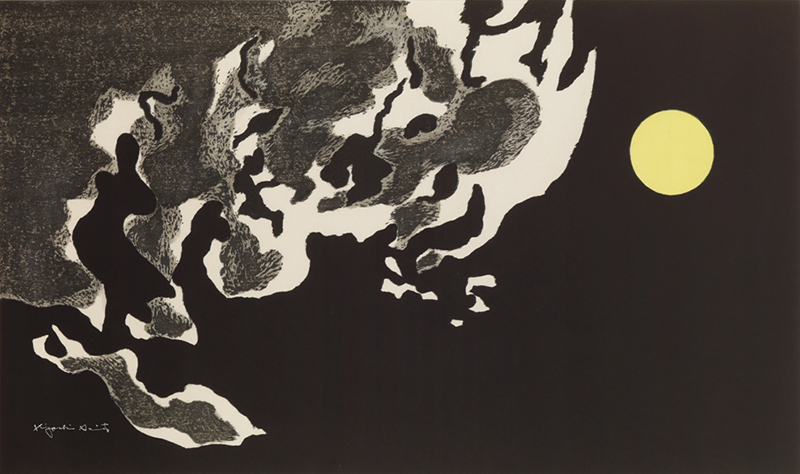

- Moon and Cloud (1)

- 1980

Woodblock print on paper

- Camellia

- 1980

Woodblock print on paper

- Resting (A)

- 1981

Woodblock print on paper

- Tenderness (G)

- 1982

Woodblock print on paper

- Spring in Kamakura, Amanawa Shinmei-gu Shrine

- 1983

Woodblock print on paper

- Door, Eisho-ji Temple, Kamakura

- 1984

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu, Akutsu

- 1972

Sumi ink on paper

- Arhat

- 1973

Sumi ink on paper

- Winter in Aizu, Takiya

- 1986

Sumi ink on paper

- Winter in Aizu (71) Wakamatsu

- 1987

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (82) Yanaizu

- 1989

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (85) Bange-machi, Unai (4)

- 1990

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (93) Kaneyama-machi

- 1991

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (104) Mishima-machi, Onobori (1)

- 1993

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (106) Nozawa

- 1994

Woodblock print on paper

- Persimmon Tree in Aizu (32)

- 1987

Woodblock print on paper

- Persimmon Tree in Aizu (37)

- 1994

Woodblock print on paper

- Persimmon Tree in Aizu (38)

- 1996

Woodblock print on paper

- The Harvest Season in Aizu (10)

- 1988

Woodblock print on paper

- The Harvest Season in Aizu (15)

- 1994

Woodblock print on paper

- Spring Adornment (1)

- 1989

Woodblock print on paper

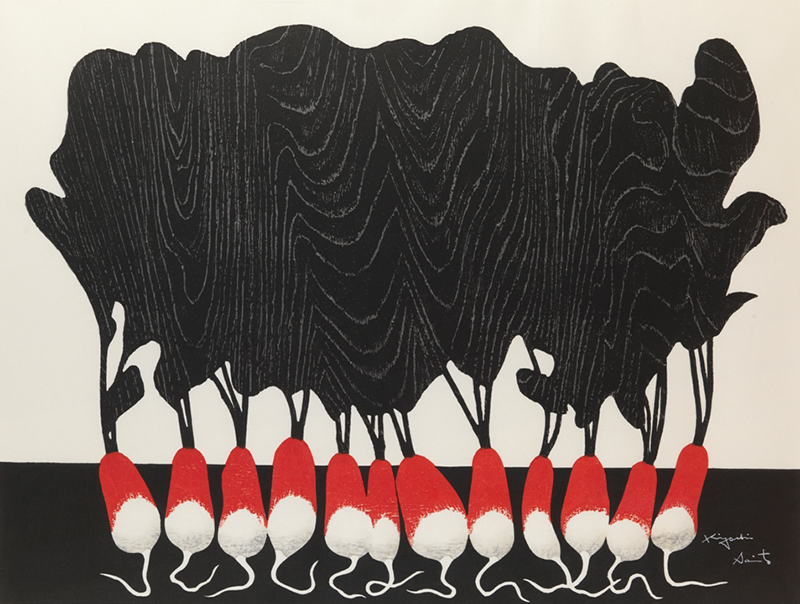

- Products of Earth

- 1989

Woodblock print on paper

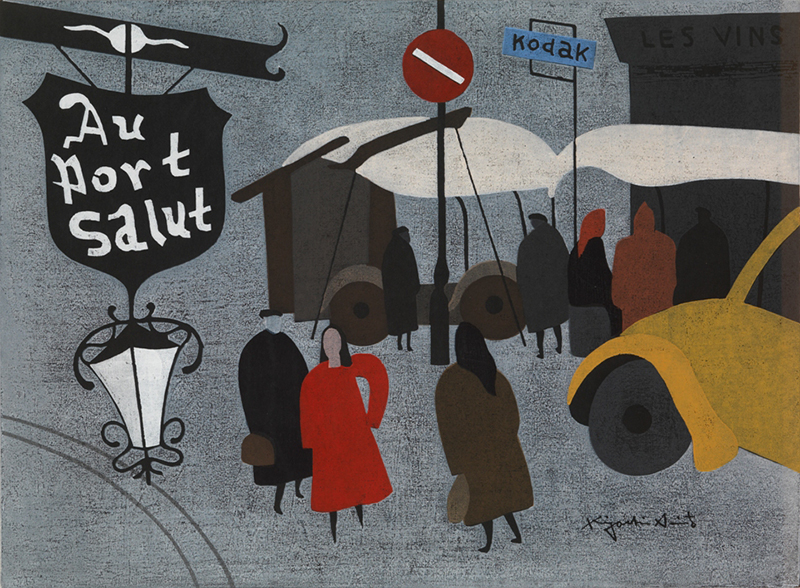

- Morning Fair, Paris (December 1959)

- 1989

Woodblock print on paper

- Paris, Stall (December 1959)

- 1989

Woodblock print on paper

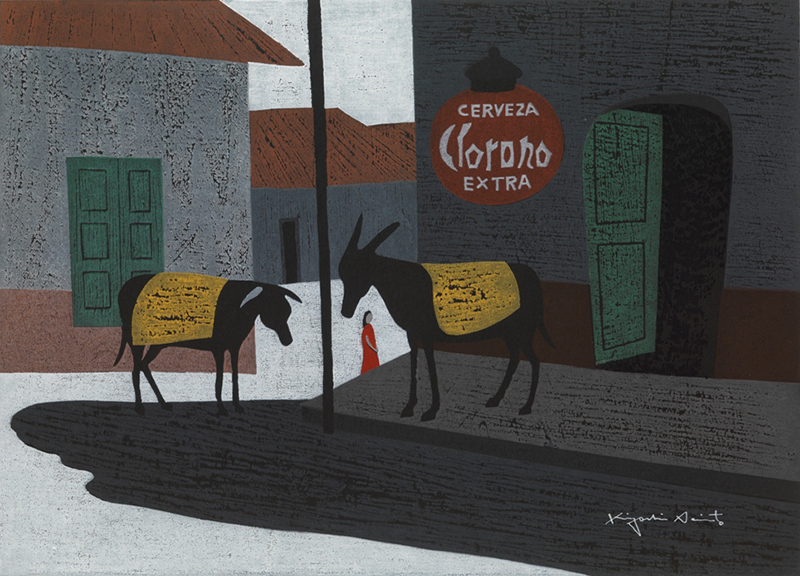

- Mexico (1956) (1)

- 1989

Woodblock print on paper

- Mexico (1956) (3)

- 1990

Woodblock print on paper

- Tahiti (1)

- 1990

Woodblock print on paper

- Dancing in Early Summer

- 1990

Woodblock print on paper

- Fan Dance (1)

- 1990

Woodblock print on paper

- Early Summer (1)

- 1991

Woodblock print on paper

- Spring Mist, Tenderness

- 1991

Woodblock print on paper

- Tenderness, Shade of Leaves

- 1992

Woodblock print on paper

- Aizu in May (6)

- 1992

Woodblock print on paper

- Aizu in May (9)

- 1994

Woodblock print on paper

- Aizu in May (10)

- 1994

Woodblock print on paper

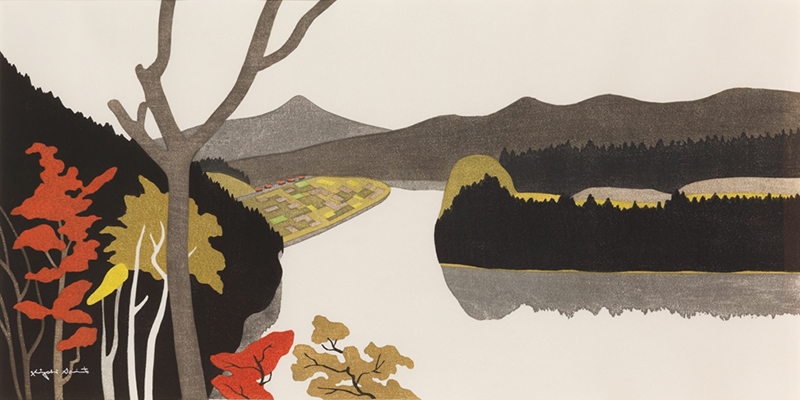

- Autumn at the Tadami River, Shimotsubaki (A)

- 1997

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (8)

- Around 1958

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (11)

- 1967

Woodblock print on paper

- Winter in Aizu (26) Kawai

- 1977

Woodblock print on paper